Ok, I admit it! It’s a misleading title. I have no idea what the “best” winter backpacking boots are, but in this post I want to share my thoughts on the subject with you.

So, here I am assuming that you have decent experience backpacking in warmer weather, and have decided to start getting out into the woods during winter. Naturally, a good pair of winter boots would be essential for the job. The first thing that most people do of course is to look online. I think you will find that the search returns very few hits. The few results that you do get, even the ones from respected organizations like the AMC and NOLS have what I believe to be very outdated, and in some ways misleading recommendations. Here I would like to explain why I believe that to be the case.

The first thing to consider is that people tend to mistakenly assume that winter boots are simply divided by degrees of warmth. So, if you know the temperature will be 0F, then you get boots rated to 0F, if it will be –40F, you get boots designed for that temperature. If someone has crossed the arctic with a particular boot, or climber Everest in it, then it must be warm, and therefore must be the ideal boot for your winter backpacking trip. I strongly believe however that there is a second criteria along which winter boots have to be separated and rated. That criteria is the type of activity which is to be performed during the trip. Temperature ratings are easy, but ignoring the differences between the intended use of certain boot designs can lead you to use boots that are warm but totally inadequate for the task at hand. I think that is an error made very often these days when looking at winter boots, and I will get to that point a bit later.

I’ll discuss temperature ratings in a bit, but first, let’s look at types of intended use for winter boots, at least as I see it. I will divide the type of use into three categories for this post, but please understand that this is a continual gradation with specific boots falling somewhere along the line. Within each of these categories, we can then examine boots of different warmth and temperature rating.

Types of Activity

Boots for stationary activity/Travel over light terrain

Such boots are designed to be soft and roomy. They are well suited for stationary activities like ice fishing or riding a snowmobile. They are also very good for travel over light terrain, perhaps while pulling a pulk. Their main goal is to provide the maximum amount of insulation. In this category I include some traditional cold weather shoes, such as mukluks.

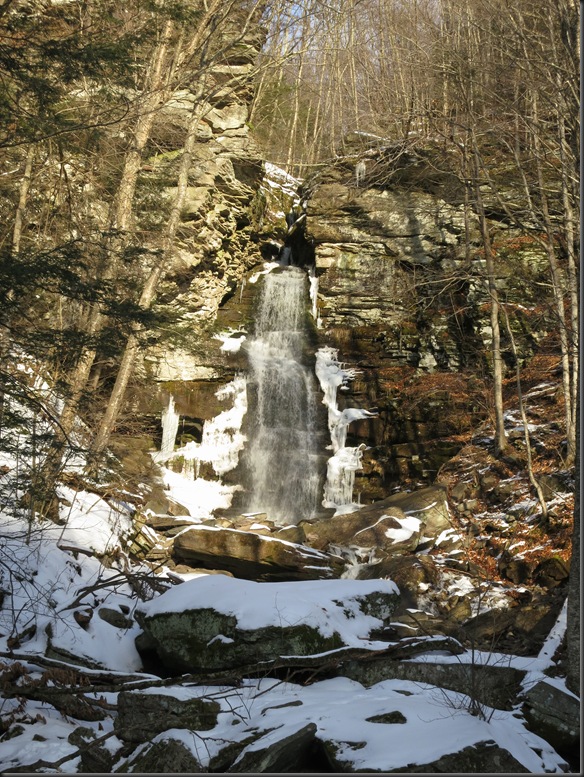

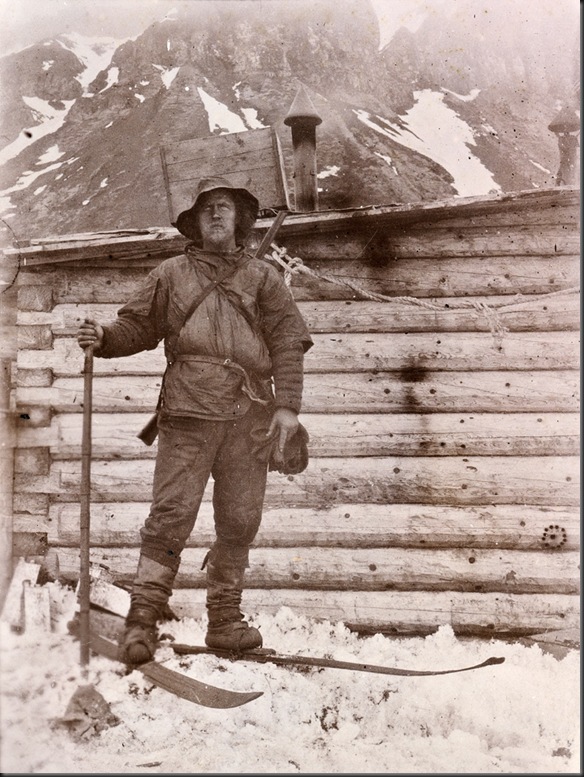

Mukluk style shoes can easily be adopted to provide great amounts of insulation. In fact, it is very easy to get a boot a few sizes larger and add insulation yourself either through a liner or just extra socks. They are very flexible which allows movement of the foot inside, which also promotes circulation and increases warmth. The big downside however is that they are horrible at dealing with moisture. Even ones made from water resistant materials like seal skin will get wet. Keep in mind that even in very cold/dry environments, the boots will get wet because of the moisture produced by your feet, which can be significant. Reading the accounts from explorers like Nansen and Scott, shows that very quickly such boots will turn into blocks of ice unless you can find a way to dry them out. The breathability of the boots becomes largely irrelevant at low temperatures because the water vapor freezes inside the boot before it can exit.

A modern upgraded version of these boots is what is often called the PAC boot. They follow the mukluk design and start with a soft, roomy, insulated boot. However, they then go on to add an outer boot which offers protection from the elements and added durability. Companies like Baffin and Sorel make good examples of this boot. Baffin for example offers boots in temperature ranges for 0F to –120F.

This type of boot offers perhaps the greatest opportunity for insulation, and can be seen worn on Antarctica and other very cold environments where travel is over relatively level and easy terrain. They have the added benefit that the inner, insulated boot can be removed so it can be dried more quickly than a boot with single body construction. When Richard Weber and Mikhail Malakhov became the first men to reach the North Pole unsupported and return successfully, they did it with a PAC style boot designed by Sorel for the expedition.

However, the greatest asset of this boot is also its main problem. The boots are soft, large and very padded. Over more difficult terrain, they start to fall short. If you leave the level snow fields and have to start scrambling over some rock, the soft boots offer very little support. It is also virtually impossible to securely place a crampon on this type of boot, which significantly limits the type of terrain over which you can travel.

Boots for travel over moderate terrain/Backpacking boots

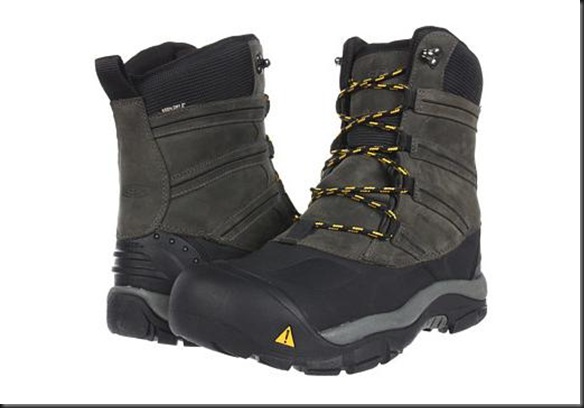

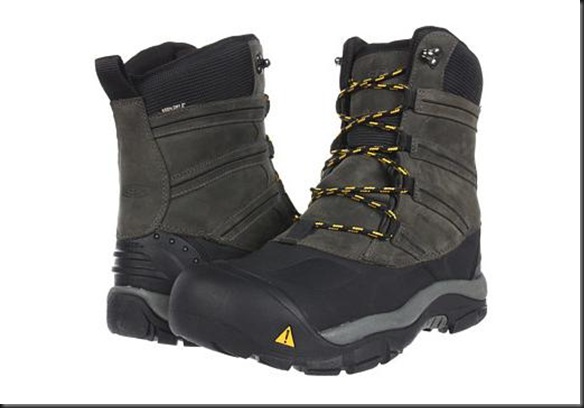

For travel over more moderate terrain, scrambling over snow, ice, and rocks, a different boot is preferable. This is the type of activity I most closely associate with backpacking. For such travel, we need a stiffer boot that offers more support not only for the ankles, but also for the bottom of the foot as well. In this category we have boots with a shank that provides rigidity, as well as a more rigid upper boot. Think of a regular backpacking boot that you use for the rest of the year, simply more insulated. A good example is the Keen Summit Country II, but other manufacturers such as Solomon and Merrell make similar examples.

Most of these boots have temperature ratings down to –40F. Their more compact and rigid construction does not allow for as much insulation as the PAC boots, but they can still be made very warm. Some manufacturers actually offer double boot versions which are similarly rigid and have the same temperature rating, but include a removable inner boot for faster drying time. The Merrell Norsehund Alpha are a good example.

This type of boot is semi rigid, so it offers good support over mixed terrain. It is also comfortable when walking over long distances because it has enough flexibility. With temperature ratings down to –40F, they also offer good insulation. They also have the very important benefit of being able to take a crampon. While you will not be able to use a fully rigid or automatic crampon with these boots, many crampons with universal attachments will work well. You will not be climbing any vertical ice with these boots, but they will perform very well over a wide variety of terrain, and they will do it comfortably.

Many winter hunting boots fall into this category. Boots like the Irish Setter Snow Claw XT offer good support over large varieties of terrain, while they have enough flexibility to keep them comfortable when walking over long distances.

Hunting boots often use thinsulate as insulation, so you will see their warmth ratings as grams of thinsulate. Generally, anything over 400 grams of thinsulate is considered a warm winter boot, although you will find boots with up to 2000 grams of thinsulate.

Technical mountaineering boots

If you have been searching online for winter backpacking boots, odds are that you have already seen that most places that discuss the issue recommend a variant of these boots. The reasoning is that if a soft boot is good over limited terrain, and a semi rigid boot is good over a wider range of terrain, then a fully rigid, mountaineering boot will be the best thing out there. After all, that is what people use to climb peaks like Denali and Everest. In my opinion that is a very misguided approach, but before I get into that, let’s go over some basics of mountaineering boots.

Mountaineering boots are designed primarily as technical climbing boots. They typically have fully rigid soles and very stiff upper construction. That is done to facilitate climbing. When climbing rock, or ice with the use of crampons, typically, you have a very small toehold, where either the tip of your boot or the crampon has caught the surface you are climbing. If the boot was soft, it would bend when your foot puts pressure on it, as it is attached to the surface at only one small point. Once it bends it will slip out. A rigid boot can take that small toehold, and turn it into a stable platform for your foot by preventing the boot from bending and slipping out. Mountaineering boots can also take a full range of crampons including fully rigid and automatic crampons. The boots can also be used without crampons to kick in steps into packed snow and ice because of how stiff they are.

For a long time the best way to achieve this was to use a double boot similar to a PAC boot, but with a fully rigid plastic outer shell. Understandably these boots are referred to as plastic double boots. Good examples include the Scarpa Inverno featured below, but a few other companies like La Sportiva and Koflach (now owned by Scarpa) make similar boots.

If you did any search online for winter boots, odds are you were directed to get a pair of plastic double boots. The thinking, as I mentioned above, is that they are extreme enough to handle anything, they are very warm, and you can remove the liners to “dry” them out in your sleeping bag.

I strongly believe that this trend in using double plastic mountaineering boots for every winter activity is very misguided and leads to use of boots that are not well suited for the task. For starters, plastic double boots vary widely in terms of warmth that they offer. Just like with any other type of boot, there are some designed for moderate temperatures (the Scarpa Omega for example) and there are others designed for climbing Everest (La Sportiva Olimpus Moons). So, if you decide to get such boots, check to see if they suit the temperature in which you plan on using them. Just because it is a double plastic boot, does not mean it will keep you warm. Second, I am a big skeptic when it comes to “drying” out gear inside a sleeping bag. From my experience, the boots will not dry, they will simply not freeze. On the other hand, they will get your sleeping bag wet. I would much rather have cold wet boots than a cold wet sleeping bag. I find this benefit of the double plastic boots to be dubious. Most importantly however, these boots are extremely uncomfortable for regular walking. They sacrifice all flexibility and comfort. For me, they are only to be used if the terrain absolutely requires them. Having to travel 10 miles a day over mixed terrain in such boots is my idea of medieval torture. Regardless of how dry I may be able to get the liners by keeping them in my sleeping bag over night, it is just not worth it.

In more recent years, there have been developments in mountaineering boots, and for most environments, the plastic double boot has been replaced by single leather/GoreTex boots. They have equally stiff soles, so they can take crampons, but they are much less bulky, and have more flexible tops. After a lot of time in them, you may even start to think that they are comfortable. La Sportiva Nepal Evo GTX are the ones that everyone seems to be using these days in the lower 48 states. They are an excellent boot. Scarpa makes an almost identical boot, the Mont Blanc. These boots also come in different temperature ratings. For example, La Sportiva Trango is designed for warmer temperatures than the Neapl Evo or Mont Blanc.

The single mountaineering boots offer the same technical aspects as the double plastic boots, but are more comfortable. The down side is that the insulation is not removable, but I find that a set of vapor barrier liners (VBL) solves that issue. That being said, they are not nearly as comfortable as any of the other types of boots outlined above, and I believe they should only be used for winter trips if serious mountaineering is on the schedule.

So, where does that leave us in the search of the best winter backpacking boots? Well, I strongly believe that the right boots for you will have to be designed for the type of activity you have in mind and they must have the right temperature rating.

The easy thing to tell everyone, and I believe rather incorrectly, is that you should get a pair of plastic double boots if you will be out in winter. I think that unless you will be in terrain that requires the use of full crampons and an ice axe, that such mountaineering boots are not just unnecessary, but also harmful. They are very uncomfortable, and if you plan on covering any distance in them, the whole trip will become torture. Sometimes, for certain trips, such boots are the only way to go. If you will be traveling over terrain that requires serious crampon use, then mountaineering boots will be required. Even then however, I prefer single mountaineering boots to double plastic boots. While the liners are not removable, the boots are much more comfortable. I find that even trips that require more technical mountaineering, are comprised of 80% regular backpacking, and 20% technical mountaineering. For those 80% the single boots wins out.

At the other end of the spectrum, many “bushcraft” experts recommend a mukluk style boot. I also believe them to be inadequate for general winter backpacking. They are ideal for certain types of terrain, as they are very comfortable and you can easily adjust the insulation inside, but their lack of rigidity, bulk, and inability to take any type of crampon, makes them hard to recommend as a good all around winter backpacking boot. If you will be traveling over relatively level terrain, or performing stationary activities, such boots are great. However if you plan on traveling over more difficult, mixed terrain, they leave a lot to be desired.

For the average person, if your winter backpacking trip is going to resemble your trips in warmer weather, than I would venture to recommend a boot that falls somewhere in the middle. A boot that is fairly rigid, so it can take some form of crampon and allow you to get a good foothold on various types of terrain, while at the same time having enough flexibility to allow you to walk long distances in comfort. Something like the Keen Summit Country II is a good choice, and if you want one with removable insulation, the Merrell Norsehund Alpha would be your best bet.

Temperature Ratings

After you have decided what boots you want to use based on the type of activity you have in mind, you then have to focus on how warm of a boot you will actually need. On one hand temperature ratings are simple-you get boots rated for the temperature you are likely to encounter. On the other hand however, the warmth of your feet depends on so many interlocking factors, that it is often difficult to select the right boot, even if the advertised temperature rating of a boot is correct.

Regardless of what boots you chose, keeping your feet warm involves a lot more than warm boots. Eating enough food, being well hydrated, and keeping your core temperature up are essential to having warm feet. Similarly, your activity level will play a crucial role in the warmth of your feet. A certain boot might be ideal in terms of warmth when you are climbing a mountain for several days, but go ice fishing with it on a frozen lake for a few hours and you might find your toes freezing.

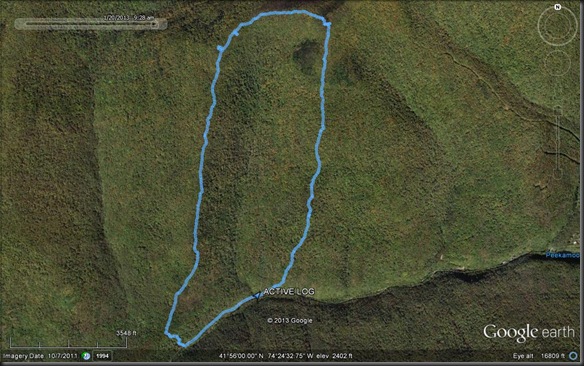

What I personally use is a combination of three boots. For warm winter trips, with temperatures above 0F (-18C), I actually use my regular backpacking boots, with thicker socks. Those boots are the Solomon Quest 4D. For colder weather I switch to the Merrell Norsehund Alpha boots. They are very warm, while at the same time having good support. They also work well with my Hillsound Trail Crampons Pro (a mild approach crampon) for moderate terrain covered by snow and ice. If I will be doing more technical mountaineering, where I will be using an ice axe, and full crampons, I use a pair of Scarpa Mont Blank boots. Now, the Mont Blanc boots are not extremely warm. They will probably be comfortable down to about 0F (-18C), or maybe a bit lower, but not much. For colder temperatures you’ll have to switch to double boots like La Sportiva Spantik, which seems to be the preferred boot for Denali. I’m not familiar with any single mountaineering boots that would be warm enough.

I know, I’m not giving you much help when it comes to temperature rating. The reason is that how warm something feels is a very personal thing. The point I am trying make in this post is that selecting boots based on warmth should only come second to selecting boots based on function. When looking for advise on boots, ask someone who does the type of activities that you plan on doing.