We can all appreciate the value of soap, but I have noticed that many manuals which provide instruction of how to make it under primitive conditions (such as the US Army manual), are so basic and simplistic that they not only make it impossible to complete the process correctly, but greatly underestimate the amount of time required for the process.

Because of the time commitment involved (could be several days to make and weeks to cure), making soap is not something easily achieved during a short camping trip, and requires a set up more similar to that of Dick Proenneke (log cabin in the middle of the woods).

There is however, an up side. Most manuals and soap recipes have in mind the production of commercial quality soap. There is a large range between such quality soap, and usable soap. This leaves a lot of room for error, while still allowing for clean dishes.

The basics of soap are water, lye and fat. All of them can be obtained in the bush.

The Fat:There isn’t much to it when it comes to usable soap. I don’t know of any organic fat that can not be used for this purpose. Compacted animal fat tends to yield the best results, but vegetable fat will get the job done, even if the soap ends up a bit soft.

Assuming you are using animal fat, probably from a kill, it will have to be rendered. To do that, cut up the fat into small pieces, place it in a container, and pour just enough water to cover the fat. Heat up the mixture, until all of the fat melts. While melted, strain it to remove any meat, and let it cool. You will find that the fat will solidify at the top of the container, while the water will be at the bottom. Remove the fat, scrape and throw away any gelatenated material and keep the fat for the next step. Keep in mind that it must be used before going rancid.

The Lye:Lye can be obtained from water and wood ash. This can be done in several ways.

The traditional way is to take a container (typically made of wood) and make a small hole on the bottom.

Do not use an aluminum container, because it will get damaged by the lye. Then take wood ash (This needs to be ash, not char coal. Take just the while stuff) and pack it into the container. Make sure it is compacted. Then boil some water, and pour it into the container. In terms of volume, think one gallon of ash, per one gallon of water. The strength of the lye can always be adjusted. Once you pour the water, you will see a reaction with the ash. Place a container under the hole at the bottom, and wait for all of the water to strain through the ash and into the new container. This part can take hours or even days.

When completed, let the liquid dry in the sun until all the water evaporates, leaving you with solid lye, which should look like salt.

The second method, which I prefer, is to take the ash, and place it in some cloth. Put the cloth with the ash in a container (make sure you have a way to hold it) and pour some hot water into the container until it covers the ashes. Then begin to move the cloth wrapped ashes up and down as you would a tea bag. Keep doing this for an hour or two (I know, not fun, but much faster than waiting a day or two). When finished, remove the ashes, and you should have your lye water. Now you can either let it dry in the sun like with the other method, or you can heat it up over a fire to speed up the process. When the water gets low, let the evaporation finish in the sun so you don’t scorch the lye.

Either way, you should end up with solid lye. Be careful when you handle lye. If it can dissolve a chicken feather (see below), it can also do a number on your skin.

As an alternative, if you do not wish to store the lye for any period of time, you can skip the evaporation step, and just use the lye liquid. Just look below for testing and mixing instructions.

The Mixing:The measurements I will offer here are just a good rule of thumb. You may have to play with it a bit depending on the ingredient you are using.

For this mixture you will need one (1) cup of water, seven (7) tablespoons of lye, and two (2) cups of melted fat.

Slowly add the water to the lye and mix it well. You can test the strength of the lye to see if it is strong enough to make soap. If it can dissolve a chicken feather, or if an egg can float in the liquid then you are good to go. (Sorry, I don’t know any ways that don’t involve a chicken) If you use the above measurements, it should be good enough. On the other hand, if you just chose to use the lye liquid, without evaporating it to get the solid lye, make sure you test the strength and use one (1) cup of lye liquid and two (2) cups of fat. The results will probably be less exact.

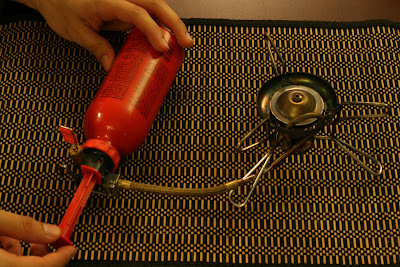

Warm up the mixture (theoretically to about 100F). Do the same with the fat, until it is melted.

Mix the lye water with the melted fat and stir the mixture until it is the consistency of melted chocolate. This can take an hour or more.

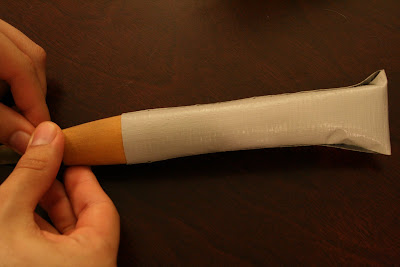

Let the mixture stand for a day or two until it solidifies. Remove it from the container and let it cure for about four (4) weeks. The reason for the curing is that otherwise the soap will still contain active lye, and may burn you.

You should now have usable soap. If not (if it separates during the cooling), you can reheat it in a water bath, stir it some more, and let it cool again.

As you can see, while all of the ingredients can be acquired in the wilderness, and the process can be completed without any special tools, it requires a stable living situation, not just a short trip into the woods. Again, the amount of time and work required will depend on the quality of soap you expect.