Not too long ago I did a post titled 18th Century Woodsmanship and Its Modern Applications. You can see it here. In that post I examined some primary sources we have about 18th century woodsmen, in particular the now famous, Long Hunters, and tried to see how their approach to the woods related to what I have called the Modern Woodsman. In particular, I wanted to see if, and how they approached long distance travel through the wilderness with man portable gear.

In this post I want to do the same thing regarding 19th century woodsmanship. More specifically, I would like to take a closer look at another well known group, the Mountain Men.

Our sources for this period are much better than for the 18th century, although the same danger of applying what we read still lurks. Once again we face the danger of looking at equipment lists and skills and trying to apply them in our context of a person who carries all of his gear on his back without that ever being the original intent or use of that gear and skills.

My very basic reading of the sources, gives me the impression that the 19th century mountain men more or less mirror the long hunters of the 18th century. They simply took the same approach to the wilderness with them to the west. The result is that much of what we see describes gear and techniques which relate to travel by horse or boat, rather than we are are searching for here, gear for the man traveling on foot.

Washington Irving provides a good description of a mountain man’s gear and his travel method in the book The Adventures of Captain Bonneville, circa 1834: “The outfit of a trapper is generally a rifle, a pound of powder, and four pounds of lead, with a bullet mould, seven traps, an axe, a hatchet, a knife, and awl, a camp kettle, two blankets, and, where supplies are plenty, seven pounds of flour. He has, generally, two or three horses, to carry himself, and his baggage and peltries.” Washington Irving, The Adventures of Captain Bonneville, 1834

Just like with the long hunters, the mountain men a century later traveled under a similar organization. They were not as many imagined lone trappers and hunters, exploring the wilderness on their own. Like the long hunters, they traveled in large groups of anywhere between 30 and 100 men, and split up only when they reached their final destination and began trapping. “It had been the intention of Captain Bonneville, in descending along Snake River, to scatter his trappers upon the smaller streams. In this way, a range of country is trapped by small detachements from a main body.... .. Two trappers commonly go together, for the purposes of mutual assistance and support; a larger party could not easily escape the eyes of the Indians.” Washington Irving, The Adventures of Captain Bonneville, 1834.

In 1841 Rufus Sage writes: "Before leaving, we were further increased by the accession of two Canadian voyageurs-French of course. Our force now numbered some twenty-four - one sufficiently formidable for all the dangers of the route." Rufus Sage, Rocky Mountain Life, or Startling Scenes and Perilous Adventures in the Far West, During an Expedition of Three Years, 1846

Many times, the trappers were accompanied by family members. In 1824 for example, Peter Skene Ogden, on behalf of the Hudson Bay Company headed an expedition of 131 people, including women and children. Specialized roles were not uncommon. Even though Jedediah Smith accompanied the Ogden expedition as a trapper, two years earlier, in 1822, he was hired as a hunter on the William Ashley and Andrew Henry expedition into the upper Missouri.

As wilderness travel during that time was generally done by pack train and in relatively large groups, it is hard to find references to individual camp kit designed to be man portable. There are good description of equipment and camp life, but it appears to be based on an outfit carried by pack train. Even so, the gear and skills used are worth a look because they at least give us a reference point for what such pack train portable outfit would look like.

During his journey to Fort Platte with a pack train under the leadership of Lancaster Lupton, Rufus Sage writes: "The Bed of a mountaineer is an article neither complex in its nature nor difficult in its adjustment. A single buffalo robe folded double and spread upon the ground, with a rock, or knoll, or some like substitute for a pillow, furnishes the sole base-work upon which the sleeper reclines, and, enveloped in an additional blanket or robe, contentedly enjoys his rest." Rufus Sage, Rocky Mountain Life, or Startling Scenes and Perilous Adventures in the Far West, During an Expedition of Three Years, 1846

Writing of his travel by pack train lead by William Sublette and Robert Campbell in 1833, Charles Larpenteur writes: “As to our bedding, it was not very soft, for we were not allowed to carry more than one pair of 3-pound blankets." Charles Larpenteur, Forty Years a Fur Trader, 1898

John Ball, when traveling with the Nathaniel Wyeth's party in 1832 states: "I had for bed purposes, the half of a buffalo robe, an old camlet cloak with a large cape, and a blanket. I spread the robe on the ground, wrapped the blanket about my feet and the cloak around me, throwing the cape loosely over my head to break off the moonshine, and a saddle for my pillow. And oh! I always slept most profoundly. We had tents, but it never raining and but little dew, we did not use them." John Ball, The Autobiography of John Ball - Across the Plains to Oregon, 1832, 1925

It appears that when traveling in the customary manner, using a pack train, each man slept with several blankets or fur robes. Some clearly found the arrangements comfortable, while others did not. Tents are also referred to, and were probably carried in group outfits, and most likely each tent housed several people. Axes, hatchets, flint and steel strikers, and kettles rounded out the camping outfit. I have not found any good primary sources as to how these tools were distributed. It is likely that each man had a hatchet and certainly a flint and steel striker with a tinder pouch, while the kettles and axes were used as group tools. To that basic camp outfit, technical trapping and hunting gear was added. The gear list provided above by Washington Irving is the most concise I have been able to find.

Even with the supplies carried by pack train, when winter came, spending the night out in the woods became difficult. Often the winters were spent in camp, but when travel in winter was necessary, the men had to improvise.

Lewis Garrand describes a night out during the winter of 1846 as follows: "We awoke on the morning of the 16th with a Norther penetrating our blankets. The river Arkansas, almost dry, and on whose north bank we were encamped, was covered with floating particles of thin ice. Drinker had but two blankets, and on awakening we found him lying near the remains of the bois de vache fire, the light ashes of which, on his clothing, gave the appearance of snow. We wore extra clothing during the morning’s ride, and Drinker looked bad from the effects of last night’s wakefulness. We rode in silence for a time, somewhat in advance of the party, in vain attempts to encourage conversation. At length, after a long pause, he said, “St. Vrain and Folger sleep together; Chad and Bransford do too. Hadn’t we better?” I acquiesced with pleasure. With saddles and over coats, we had good pillows-the other clothing remained on us. Wherever camp was made, a place was selected by each couple for sleeping before dismounting (mountaineer custom); and, ere dark, the pallet of robes was always spread. We huddled around the miserable “cow wood” fires, chilled by the cold winds." Lewis Garrand, Wah-to-yah and the Taos Trail, 1850

Rudolph Freiderich Kurtz writes in 1846 writes: "We spread our apischimos on the ground out on the open prairie and covered ourselves with riding cloaks and buffalo robes.... We called to our dogs to lie on top of us, as usual, for the purposes of keeping guard and also of imparting warmth. But those canines were every instant scenting nearby wolves, bounding off with great outcry to fight the beasts or drive them away, then lying down on top of us again, scratching themselves and contesting one another's places. Under such restless, disquieting conditions, especially in our overexcited state, we were unable to sleep at all." Rudolph Freiderich Kurtz, The Journal of Rudolph Friederich Kurz, 1970

In a more of an emergency winter setting, in 1840 Charles Larpenteur writes: "The mules were soon harnessed up, and into the hard storm we started, with but one Indian, who was my guide. It was an awful day; we could see no distance in any direction, floundered in deep snowdrifts, and knew not where to go for timber. But our guide was a good one, who brought us to a small cluster of scrubby elms. The snow had drifted so deep that we could find no dry wood and had to go to bed without a fire. We made ourselves as comfortable as we could by digging holes in the snow for shelter." Charles Larpenteur, Forty Years a Fur Trader, 1898

So, where does that leave us? Well, speaking very generally, there is quite a bit of difficulty is looking at gear and skills from this time period and applying them directly to a more modern approach to travel in the woods. It is hard to directly create a one to one substitution of gear and skills because most of the sources we have deal with a set up designed for travel with a pack train, most often in large groups. Taking that same gear and trying to use it for a single person traveling alone on foot, is very challenging.

I have not been able to find any primary sources of what gear would have been carried by a lone person traveling on foot. I imagine it was done, and there are probably sources on the subject out there, I just haven’t been able to find them.

At this point however, we have to look at an interesting transformation, which offers a different perspective and approach to the wilderness, and has been much more impactful on our current approach to the wilderness, than the exploits of the mountain men.

In the later part of the 19th century, a new group of outdoorsmen emerges. Up until that point, most writing regarding the wilderness, and therefore the expeditions and the related gear and skills involved, were directly related to work. The Long Hunters, the Mountain Men, loggers, trappers, hunters, etc, all went into the woods to make a living. Being in the woods was work. Certainly people must have enjoyed the woods, and gone there recreationally, but the main focus was a commercial one. As a result, what primary sources we can find, are not directed at educating the average person about the wilderness, but were created either as personal journals, or as commercial propaganda.

In the later part of the 19th century however, we start to get a large and dedicated group of recreational outdoorsmen, who are a lot more interested in providing instructional information on how a single person can go into the woods on foot, and stay there. Much of the information we find in these sources is based on what those commercial woodsmen of previous decades had learned, but was much more tailored to how we currently relate to the wilderness.

Good examples from this time period are John Muir and George Washington Sears (Nessmuk). In 1879, John Muir writes Travels in Alaska, and in 1884 George Washington Sears writes Woodcraft. The approach taken by these woodsmen in the later part of the 19th century is quite different from that of prior decades. The difference is not a technological one. Pretty much the same gear was available in 1832 as was in 1884. However, the way that gear was used and prioritized, changed. The focus shifted from how to equip a large group of men so that profit from an expedition can be maximized, to how to allow a single person to travel through the woods while carrying his own gear in the most comfortable way possible. This shift, combined with innovations in technology, will eventually lead to our modern approach to the wilderness.

This transition was not easy, and required a lot of trial and error and at times suffering. We often assume that people like Nessmuk were well versed woodsmen, but we shouldn’t forget that he was making things up as he went along. He was taking gear and skills from woodsmen for whom the wilderness was a commercial enterprise, and was attempting to apply it to his own woodsmanship. That is why he is so often critical of those who came before him.

These authors, still have one foot in the past. Even going into the early 20th century, most books related to the outdoors, still had extensive discussions on travel by pack train or canoe. Travel on foot, alone, was still a tricky subject, filled with risk.

Even though John Muir’s writings are not instructional in nature, we can get a glimpse of that in a few places.

“It was now near dark, and I made haste to make up my flimsy little tent. The ground was desperately rocky. I made out, however, to level down a strip large enough to lie on, and by means of slim alder stems bent over it and tied together soon had a home. While thus busily engaged I was startled by a thundering roar across the lake. Running to the top of the moraine, I discovered that the tremendous noise was only the outcry of a newborn berg about fifty or sixty feet in diameter, rocking and wallowing in the waves it had raised as if enjoying its freedom after its long grinding work as part of the glacier. After this fine last lesson I managed to make a small fire out of wet twigs, got a cup of tea, stripped off my dripping clothing, wrapped myself in a blanket and lay brooding on the gains of the day and plans for the morrow, glad, rich, and almost comfortable.” John Muir Travels in Alaska 1879

“That was a wild, stormy, rainy night. How the rain soaked us in our tents! Our Indian neighbors were, if possible, still wetter. Their hut had been blown down several times during the night. Our tent leaked badly, and we were lying in a mossy bog, but around the big camp-fire we were soon warm and half dry.” John Muir Travels in Alaska 1879.

“My general plan was to trace the terminal moraine to its extreme north end, pitch my little tent, leave the blanket and most of the hardtack, and from this main camp go and come as hunger required or allowed.” John Muir Travels in Alaska 1879.

When George Washington Sears wrote Woodcraft in 1884, he considered his seven day trip alone through the woods significant enough that he dedicated a whole chapter of his book to it. The rest of the time, he continued to travel by canoe, so gear used on those trips probably more closely resembles that of earlier decades, even though tailored for a single person. The items he took on this seven day solo trip were: rifle, hatchet, compass, blanket-bag, knapsack, knife, one loaf of bread, two quarts of meal, two pounds of pork, one pound of sugar, with tea, salt, etc. and a supply of jerked venison. One tin dish, twelve rounds of ammunition and bullet mold. For more information, see the gear list here.

The personal camp outfit was starting to resemble what we are accustomed to today: a backpack, a small tent/tarp, a blanket, small pot, hatchet, knife, fire starting devises, compass, etc.

This trend and development in gear and skills, continued into the early 20th century. In 1906 Horace Kephart published Camping and Woodcraft, and in 1919 E.H. Kreps published Woodcraft. Both books provide great detail on the necessary skills and equipment for the solo person traveling on foot through the woods. You can get more detail on Kephart’s gear here, and on Kreps’ gear here.

Due to the technological limitations however, those authors still remained connected to the skills and methods used by the woodsmen from earlier decades. The blanket was still to best form of insulation available, dictating much of the remaining kit list. The weight of wool blankets made it impossible for the person carrying his gear on foot to carry sufficient insulation to stay warm in colder temperatures. Buffalo robes and furs were out of the question with minor exceptions. Wood processing tools were still of primary importance because of the reliance on fire created by the available insulation.

Much like in earlier dacades, winter camping was considered undoable without keeping a fire going through the night. In Woodcraft Nessmuk writes “Of course nobody could stay in an open winter camp without an axe.” George Washington Sears, Woodcraft, 1884

In the later part of the 19th century, outdoorsmen were sitting at the cusp of a transition, which would take us from the skills and equipment familiar for decades and centuries before, and push us into the methods and equipment to which we are accustomed today. It began with the transformation with gear and skills so that they would better accommodate the solo traveler, whether he be on foot or a small canoe. The next step was to transition to skills and equipment which allowed that solo traveler to sever his reliance on the fire for survival.

This first stage of the transformation is exemplified by people like George Washington Sears, Horace Kephart, and E.H. Kreps. Even though Kephart and Kreps are writing a bit later, they are describing tools and techniques in existence during earlier decades. Those men used kit which was man-portable, fit in a backpack, and allowed a single person to travel unimpeded through the wilderness. All of them however, remained connected to the old methods of camping. Spending the night out without a fire was still not a reality. Sizable tents and sleep systems were still the norm. The best description of this for of wilderness travel and living I have found is summarized by E.H Kreps: “Since the entire camp outfit and food supply must be carried on these journeys, the outfit taken must of necessity be meager. Only a single blanket and a small, light canvas shelter can be taken and to sleep without a fire under such conditions is out of the question. A good hot fire must be kept going and such a fire will consume nearly half a cord of wood during the long northern night.” E.H. Kreps, Woodcraft, 1919

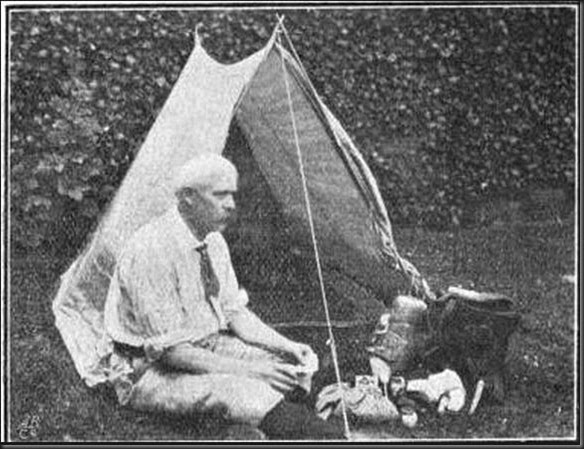

The above picture shows a camp set up by Horace Kephart.

Changes however were beginning to occur, which would directly lead to our modern way of interacting with the wilderness and allow for the second step of the transformation. Speaking of technology already in existence prior to 1906, Horace Kephart writes: “Bedding is the problem; a man carrying his all upon his back, in cold weather, must study compactness as well as lightness of outfit. Here the points are in favor of sleeping bag vs. blankets, because, for a given insulation against cold and draughts, it may be so made as to save bulk as well as weight.” Horace Kephart, Camping and Woodcraft, 1906

Even though Kephart wrote about and appreciated the technological changes taking place around him, he still remained determined to incorporate them into the familiar methods of camping known from past decades. Even when recognizing the benefit of the sleeping bag in the above quote, he writes right after: “…the weight need not be over 8 pounds complete. Your camp fire will do the rest.” Horace Kephart, Camping and Woodcraft, 1906

Kephart however, gives us a glimpse into the second step of the changes which would eventually lead to our current approach to the wilderness. According to him, this phase began in 1865 in England, with what he calls the Scotchman Mcgregor. The gear and corresponding skills that emerged across the Atlantic during that time would complete the transformation into our modern approach to the wilderness. Kephart writes of numerous set ups created in that fashion, which were small, lightweight, and self contained, such as the ones made by Owen G. Williams of J. Langdon & Son, which weighed only 7 lb total, including a tent and sleeping bag. The significance of this new equipment however, is not so much the weight or lack of bulk; it is the approach they allowed one to take to the wilderness.

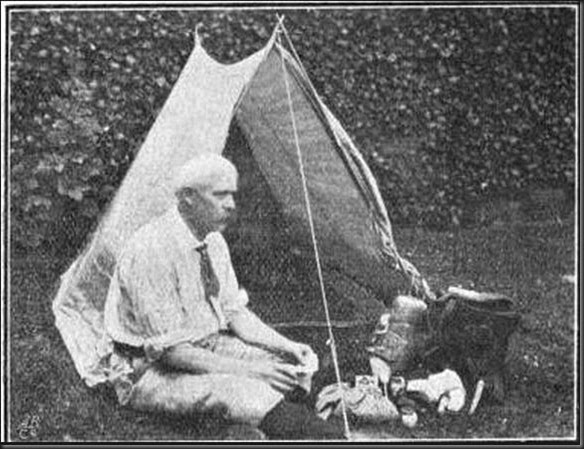

The above picture is from The Camper’s Handbook by T.H. Holding, 1908

Most significantly, they allowed a person to stay in the wilderness without being reliant on a fire. With this new gear and techniques, one could now spend a winter night out in the woods without having to rely on a fire. Small enclosed tents, and down sleeping bags of compact design (described as having small foot boxes like a mummy sleeping bag) made that possible, and with the use of a portable stove, one could cook within the shelter as well. One of course could still make a fire each evening, but survival was no longer linked to it. “I am assured that this midget shelter will stand up in a hurricane that overthrows wall tents, marquees, and the army bell tent. Enthusiastic campers use it even in winter, sleeping out without a fire when the tent sags heavy with snow. Since the English camper seldom could get wood for fuel, he was obliged to carry a miniature stove and some alcohol or kerosene.” Horace Kephart, Camping and Woodcraft, 1906

It would be quite some time before these fully modern way of camping reached America. The delay seems to have been the result of cultural differences and the fact that those camping methods were developed for areas that were considered relatively civilized. Kephart rejects these outfits as inadequate for camping in America, but his reasons seem more like excuses. He states: “The bedding here described would not suit us at all. The down sleeping-bag would be too stuffy. In England, I suppose, it is taken for granted that the camper will procure, for each night, a bedding of straw and hay; but in our country, there are many places… where the camper would have to chance it on bare ground.” Horace Kephart, Camping and Woodcraft, 1906 The “stuffy” sleeping bag is nothing more than a personal preference, not a limitation in the woods, and his assertion that there is no ground cover is interesting in light of him carrying a browse bag exactly for that purpose. I imagine many woodsmen accustomed to the older methods remained similarly resistant for quite a while.

So, as a brief overview, the 19th century brought very interesting changes with respect to your approach to the wilderness. In the early 19th century, the methods and equipment were very similar to those used in the 18th century, and show clear continuation. In the later part of the 19th century however, people began using those same methods and equipment developed in earlier decades, and applying them to individual travel through the woods on foot, for recreational purposes. At the same time, in Europe, and later in America, those developments were further pushed to create not only new gear designed for a person traveling through the woods on foot, but also to allow that person to do so without a direct reliance on the old methods. Small tents and down sleeping bags, along with portable stoves, allowed a person to sleep through the night without reliance on a fire. Not only the equipment, but also the methods involved had shifted, and gave us what we see today.

Anyway, those are my observations based on the limited research I have done. Hopefully it has been entertaining.

![289[3] 289[3]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgHPJPeGM2f7cd5GzssP23qG1EUVedjO9aQ-WwosPRkx6AaiIFa6csaZYG0l6VWumss-KWSheM3XaaJsUiyy8D7S9XXZPtMUABsn01l2CQcP9WRCEttQRcW0qA6M4KFVSuIsE9qqkgBN1o/?imgmax=800)