Winter has come! For many, it signals the end of camping and bushcraft until spring. For may others, even experienced outdoorsmen, it signals a change in camping and bushraft. Backpacks get replaced by cars, snowmobiles and toboggans, loaded with a ballooned gear list, of large tents, wood stoves, and copious amounts of clothing. To a person who is thinking of venturing into the woods during winter for the first time, the task seems daunting, requiring that one either gives up on the idea, or else acquires large amounts of new and different gear, as well as adopt new methods of camping.

Well, I decided to write this post to tell you that winter camping is not some extreme pursuit, nor does it require a change in the way you camp. In this post I hope to go over some of the considerations regarding techniques and gear for moderate winter camping. By moderate winter camping, I mean wilderness pursuits that do not require specialized skills, i.e. no ice climbing our mountaineering, no glacier travel, etc.

A while back I did a post called Beginners Guide to Affordable Bushcraft and Camping Gear. In there I provided a list of links to other articles that I have done on beginners three season camping and bushcraft. In this current article, I will be building on those foundations.

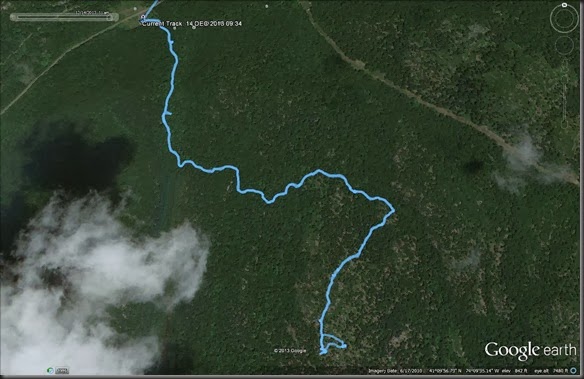

Before you continue reading, please remember that what you see here is my style of winter camping. It is certainly not the only one, and it is not for everyone. For me winter backpacking, camping, and bushcraft are not different than in any other season. My focus is on mobility and portability of gear, in order to facilitate travel over difficult and diverse terrain. My winter camping mirrors my three season camping. I backpack into the woods, sometimes for a considerable distance, until I reach the chosen location on the map. I then set up camp and spend the night there. In the morning I pack up and get moving again. You can see my trip reports for more details. So, when you read this post, keep that in mind. My way is certainly not for everyone. If you are looking for information on traveling with a sled, and staying in large canvas tents, heated with wood stoves, you will not find my approach very useful. You can find numerous good sources of information on that style of camping. In this post however, I want to tell you that you are not restricted to that style of camping, and that there is another way. If like me, you are interested in being able to comfortably carry your winter gear in a backpack, and travel over diverse terrain where a sled will not go, or to places where there is no fuel for the wood stoves, or simply want to get into winter camping without a huge investment in gear, then hopefully this will be of some help.

The last thing I will say before starting the gear discussion is that you should make every effort not to use the fact that it is winter to forget everything you have learnt about gear selection and woodsmanship. Winter is no excuse to pile up every imaginable piece of gear “just in case”. Your gear selection process should be no different than when doing it during any other time of the year. After all, if you were out camping in 35F (2C) in the fall, how many changes are required to do it at 20F (-7C) in winter? What about at –10F (-23C)? The difference is one of degree (excuse the pun) not of kind.

The easiest way to start winter camping is to just do it. That is how I started. Little by little, you will figure out your own little methods and tricks to make the stay more comfortable, but the basics are not that different. When starting out, don’t go too far into the woods, and don’t go out in temperatures much lower than what you are comfortable in. Gradually you will be able to push your own boundaries, and most importantly, overcome your fear and need to bring out excessive amounts of gear just because “it is winter”.

Clothing:

Perhaps the most important consideration in winter camping is your clothing. In my opinion, the most important thing to realize about your winter clothing is that it is not that different from your three season clothing. Now, that is contrary to most of the conventional wisdom that you will see in many books and websites. If you have been reading on the subject, by now you have become familiar with people dressed like spacemen, with numerous layers, anoraks, heavy coats, etc. This type of clothing might be excellent for car camping, snowmobile travel, pulling a toboggan or sled along a frozen river bed, or for sitting by the wood stove inside a spacious tent, but it is horribly inadequate for the type of winter woodsmanship I am discussing here. A woodsman who is mobile, and travels through the woods on foot, carrying all of his gear on his back, requires a different clothing system, and it closely resembles that of a backpacker during the rest of the year.

Your winter clothing system is not complicated, and it does not require you to purchase a whole new set of clothing. Since your winter trips will resemble your three season trips, the clothing is surprisingly similar. Your winter clothing is comprised of your three season clothing, with the addition of one, or possibly two pieces.

I find that people almost always underestimate just how much heat their body produces when working and traveling through the woods, even if the travel does not involve any special or extreme exertion. To account for this heat production, and prevent getting drenched in sweat, the approach I use focuses on creating what some call an “action suit”, which will allow you to remain thermally neutral during periods of high activity. Just like with your three season layering system, you have a wicking base layer, an insulating layer, and possibly a shell layer to protect you from snow and wind. The insulation in the action suit is supposed to be the minimum required to keep you thermally regulated when moving. In most conditions that requires very little because even in extremely cold conditions the body produces very large amounts of heat. It is not uncommon to see people skiing to the South Pole in just a base layer. If you wear all of the three season clothing that I listed in the post to which I linked earlier on Beginners Guide to Affordable Bushcraft and Camping Gear, you will most likely end up being too warm. It will serve you as an action suit in even very cold conditions, and in most cases you will have to end up using it without the secondary fleece layer. A possible additional piece of clothing you may want to use in this action suit, aside from your three season clothing is a pair of thermal long johns. I find them unnecessary in all but the coldest conditions, but you may feel better with a thin pair like the Patagonia Capeline 1 thermal underwear.

![012[3] 012[3]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgP2UyV_rOevne49jC64TKvo1QFtDg0VqP-vf3K65ZhUb6KcsRaXrHJ-D4yh3KfBUlAfoV5K8rAMasjTWphTQQ03eFl3jHYRC2pqA0e9t_AILzElU8Glys5PNh3piXOY_IDb4eO7oCmk4M/?imgmax=800)

Now the question of course comes, “what happens when you stop moving”? That is where the additional clothing comes into play. When you stop being active, let’s say when you are done setting up camp, and sit down to cook dinner, your body heat production drastically decreases. To compensate for that, you need a thick outer jacket that you can put on on top of all your other clothing.

However you want to think of your clothing system, whether it be in the way I have described, or simply as wearing a lot of layers to keep warm, the reality is that during most of your trip, your heavy insulation will not be worn, but rather stored in your backpack. As I mentioned earlier, when you are active, your body will produce a lot of heat, which means that ultimately, you will be wearing very little clothing. As a result, bulky and heavy parkas of decades past simply will not do for the style of winter camping I am describing here. The moment you start moving, you have to remove that jacket and place it in your pack. If you can not do that because of the size of the jacket, then it is not much good. The ability to pull out the stationary/heavy insulation and put it on the moment you stop moving, and subsequently take it off and quickly pack it away once you are ready to move on, and do it in an efficient and fluid manner is of extreme importance. This outer coat has to be not only warm (a task easily achieved), but also very compressible and light weight. That is not a concern for someone who is car camping, or traveling on a snowmobile or with the use of a sled, but for the woodsman carrying his gear on his back, it is of paramount importance.

I have written all of the above, just to say that all you need when it comes to your winter clothing is your three season clothing (wicking base layer, insulating thin fleece layer, thicker fleece or puffy layer, rain shell) and a big puffy jacket which is light and easily compressible, so that it can be stored in your pack while moving, and put on while you are stationary. The jacket I use the most is the Patagonia DAS Parka. I find it offers good insulation for most weather conditions while compressing well and having reasonable weight. There are many other good options currently on the market, which utilize all types of fill, some synthetic, some down. Ultimately, the exact materials are not crucial. They have all been used successfully by experienced woodsmen. You just have to make sure the jacket you get is warm, and that it can compress easily to fit in your pack once you start moving.

The only other thing to touch on, aside from the obvious – bring a hat and gloves, is winter boots. Again, there is a lot of talk about mukluks, pac boots, and all sorts of designs, but in my opinion, they are either inadequate or complete overkill. For most winter conditions, your regular backpacking boots with a good pair of wool socks will serve you just fine. Unless you are going out in some extremely cold conditions, or climbing ice, nothing more specialized is needed. Remember, there is no need for your winter trips to drastically differ from your three season ones, and as a result, very similar footwear will be needed. Do not be tempted to buy heavily insulated soft boots (mukluks) which are designed for travel on level ground, or specialized mountaineering boots, designed for ice climbing. Both tend to be inadequate or overkill for travel over diverse terrain.

Lastly, related to the boots, is a pair of good gaiters. Gaiters attach to the boots, and go up your leg (I would suggest knee length ones). They keep snow out of your boots, and keep snow off your pants. I use a pair of REI Havenpass eVent gaiters.

For a more in dept look at what I use, you can have a look at the following posts:

Ultimately, my advise is - don’t over think it. You have been out during winter before; you have been in the woods during cold weather. Dress warmly, be smart, and you will do just fine. If you find your clothing to be inadequate, turn around and go home. Don’t get caught up in gimmicks about the perfect material or the perfect clothing, whether it be the most modern miracle fiber or some alleged sacred knowledge of someone’s ancestors. Most options available on the market have been thoroughly tested and work fine. The things I mention above are just tips designed to make your trip easier, and to ensure that you remain mobile while in the woods.

Gear:

Just like with your winter clothing, your winter gear does not have to drastically differ from your three season gear. If you are reading about winter camping, I assume that you have at least some experience with three season camping and have the appropriate gear. If you are unsure about your three season gear, have a look at what I use:

Your winter gear will simply reflect some modifications to your already existing three season gear. As I said earlier, do not be tempted to use “winter” as an excuse to pile on gear. Any changes will be in degree, not in kind.

Shelter:

The first modification which will be needed is to your shelter. I strongly believe that your shelter system should be capable of keeping you comfortable during winter without the help of external heat sources. Having a fire for extra warmth is a nice thing, but with the technology we have at our disposal today, there is no excuse for being reliant on such external heat sources. If your shelter system is not capable of keeping you comfortable, let alone alive on its own, then I would recommend you take a long, hard look at your gear choices. From my experience, not much is required to meet these criteria.

Your shelter is comprised of three elements: the tent/tarp, the sleeping bag, and the sleeping mat (or if using a hammock, an underquilt).

When it comes to a tent/tarp, winter camping can be accomplished with just about any variant. As you know, my preference is for an open floor tent. That way I do not have to clean snow from the floor, while at the same time, I get good wind protection. That being said, most tents, or a low pitched tarp will get the job done. People often go over the top and immediately get a “four season” tent. The reality is that unless you are climbing Denali, or crossing a glacier, such a tent is not needed. Tents like that are designed to withstand extreme winds and snow fall, conditions you are unlikely to encounter on a regular winter trip. Most three season tents, or a well pitched tarp will handle the conditions without a problem. The shelter you use for your three season camping will be sufficient for most winter use. If you are an area where the winters are so extreme that a regular shelter can not survive, then you don’t need my advice on the subject.

The sleeping bag is a different matter. You need one with a proper rating. As you know from your three season trips, sleeping bag ratings are subjective, but try to be within the range of temperatures you are likely to encounter. This may very well necessitate that you buy an additional sleeping bag. However, be honest with what you need and what you already have. Have a quick look at the winter temperatures in your area, and then have a look at the temperature rating of your three season bag. There is a good chance that you already bought a three season bag with a 15F (-10C) rating, just in case. If winter temperatures in your area rarely drop below 20F (-7C), then is there a need for a new bag? Do not be tempted to go out and buy the heaviest arctic bag you can find. Remember, everything you bring has to be carried in your backpack, not to mention that it costs money. There is a good chance you may be able to manage just fine in winter with your three season bag, or by simply adding a cheap fleece liner which you can buy in most outdoor gear stores. If you do in fact need a dedicated winter bag, there are many good choices on the market. Just like with jackets, they are made in all sorts of materials, with all sorts of fill, from synthetic to down. All of them will work fine for our purposes (here I am assuming a standard design mummy sleeping bag). The general rule of thumb is that the less a bag costs, the heavier and less compressible it is. You will have to find your own balance on the budget v. weight scale.

Your sleeping mat is also very important. Insulation from the ground will make a big difference, especially in winter. Sleeping mats come with an R rating. On the US scale, a R rating of 4 and above is considered appropriate for winter camping. Not too long ago, the only available pads were closed cell foam ones. Back then, in winter we used to simply bring two closed cell foam pads, which had a R rating of about 2 each. The same approach works just as well today. Whatever pad you use for your three season camping, can be converted for winter use with the addition of a closed cell foam pad underneath. If you have the cash to spend, there are pads on the market today with high R ratings. I use a Therm-a-Rest Neo Air XTherm, which has an R rating of over 5. I use it for my three season camping as well because it is light and packs down very small.

That’s all there is to it. The only other tip I can give is to use a pee bottle. Having a dedicated bottle in which you can pee during the night without having to get out of your sleeping bag makes a huge difference. Every time you get out of your sleeping bag, you lose all of the accumulated heat, which you then have to spend time re-establishing. A pee bottle will keep you much warmer. I use a collapsible Nalgene bottle for the purpose.

There are other additional tips, such as carrying snow stakes for easily securing your shelter in snow, or bringing a small piece of closed cell foam to use as a seat, but those are all things you will work out along the way.

Water Storage and Purification:

Another part of your gear which will require modification is your water storage and purification equipment.

The first aspect that might need to be modified, is the water containers which you use. It is preferable to use wide mouth bottles and containers, which will reduce the likelihood of the water freezing the bottle closed. Your standard Nalgene bottles work well, as well as the wide mouth collapsible bottles made by Nalgene. I stay away from hydration bladders altogether because the water freezes in the tubes way too easily. Some people have managed to make hydration systems work by insulation the system, but I prefer to stick to regular bottles. One 1L Nalgene bottle and one 2L collapsible Nalgene bottle serve me well on virtually all trips. At night, if you expect low temperatures, keeping the water bottles in your sleeping bag is a good idea. In the alternative, burry them in the snow. The water will be cold in the morning, but will not be frozen.

The second, and more significant change is the water purification method. Unfortunately, most filtration and purification devices fail in winter, or seriously underperform. Filters are at the greatest risk. Once they get used, the water trapped inside the fibers or ceramic element is at great risk of freezing. Once that happens, the filter element will be damaged, making the filter of little use. Chemical treatments like Aqua Mira still work, but in cold weather they are significantly slowed down. Make sure to follow the instructions for cold weather use. Additionally, I prefer water purifiers in solid form rather than liquid, due to tendency of liquid water purifiers to freeze. UV devices like Steri Pen work just as well in the cold, but their batteries die much faster. Make sure to account for that.

All of this however is not as large of an issue as it might first appear because in winter, liquid water is hard to come by. Most often, you will end up melting snow or ice for water. As such, it is easily purified by boiling. Of course, that will require you to bring adequate amounts of fuel. This is what I do. I also bring a few chemical treatment tablets, in case I want to save fuel.

Stove:

The first change to the stove you use, is what I mentioned above – you will simply need more fuel. Melting water requires fuel (unless you have a fire), and cooking in cold weather uses up more fuel. Make sure you plan accordingly, but don’t go overboard. After your first or second trip you will know how much fuel you use per day, and you can make more accurate calculations.

The second change is to the stove itself. While most stoves can be pressed to give some type of service during winter, an efficient stove has to have certain features. The main issue with most stoves commonly used during three season camping is the fuel they utilize, and how they utilize it.

Alcohol stove, which work great for three season camping, struggle in winter. Since alcohol requires vaporization in order to burn, it has to be heated before it combusts. While that is not difficult to do, the heat generated, is often very inadequate. You can easily have a stove working at full blast, while the water never coming to a boil. Even if it does, you will use large amounts of fuel.

Stoves which use pressurized fuels in a canister equally suffer in winter. Those small stoves like the MSR Pocket Rocket, which mount on top of a fuel canister require pressurized gas in order to operate. The problem is that in cold weather, most of those gases remain liquid, failing to gasify and generate any pressure. Even the best fuel mixes, like those used by MSR, which are 30% propane and 70% isobutene have a hard time working. Propane will work in cold weather, but will get used up quickly. The remaining gas mixture, will not readily gasify. The solution is to use a remote canister stove, which has a vaporization tube, allowing for inverted canister use. In effect, by inverting the canister, you begin to use the fuel in its liquid form. The liquid fuel passes through the vaporization tube, turns into gas, and is then used by the burner. I use the Kove Spider stove all year round, which is of this design. The MSR Wind Pro is another good option.

Lastly, you can get a white gas stove. Basically, these stoves run on a liquid petroleum based fuel. It is pressurized by a hand pump. Then, much like with the remote canister stove discussed above, the fuel passes through a vaporization tube, before being used by the burner. Both MSR and Primus make good stoves of this design. Such stoves can operate in any weather, even in extreme condition. They produce a lot of heat, but in turn tend to be heavy.

All that being said, just like with most other gear, you can probably make due with less than ideal equipment. Regular canister and alcohol stoves get taken out during winter all the time. Clearly with some care they can be made to work. Simply keep in mind what I have told you here, so you are not surprised when the performance is less than expected or more care than usual is required.

Other Specialized Winter Gear:

The above changes to your gear, I consider essential to winter camping and bushcraft. There are other items which I consider non-essential for beginner winter camping. They are nice to have and will expand your range and capabilities, and after you have spent some time in the bush, you will decide which ones you need, but there is no need to get any of them when first starting out. Such items include snow shoes, crampons, ice axes, regular axes, saws, etc. I can dedicate a whole post on each piece of gear, as there is much to cover, but that is beyond the scope of this post, or your need as someone who may just be starting to camp in winter.

Snowshoes make travel in deep snow much easier, and recent developments in snowshoe technology have made them efficient, and easy to use tools. However, they are not essential. If the snow is deep, you simply will not be able to go as far into the woods as you originally planned. For the beginner, that might not be a bad thing.

Crampons, properly fitted to the shoes you use, are also great tool, and so is the corresponding use on an ace axe. However, unless you are climbing some serious inclines, you can get by fine without them. Be careful in icy conditions, take your time, and cover less distance. If you want a bit more traction, a simple device like the Kahtoola Microspikes which slide onto your boots, will work very well for a normal trip.

Axes and saws are similarly thought of as essential to winter camping and I keep seeing larger and larger variants being carried, but I do not believe them to be necessary. As I mentioned when it came to the shelter system, I strongly believe that your gear should be sufficient to get you into the woods, let you stay there in relative comfort, and get you safely out, without the need for external heat sources like a fire, or any other type of shelter or tool building. These tool remain in our consciousness from a time when technology was in such a state that a fire during the night was what kept you alive. That is no longer the case. If your gear does not allow you to complete your trip without necessitating the construction of any devices or reliance on a fire, then I would recommend that you take another look at it. Don’t get me wrong, I like having a fire. It makes things more comfortable; but I do not need it. I have means to cook my food, melt snow for water, and keep myself warm at night without the need for processing large volume of firewood. I also understand if an experienced woodsman wishes to impose such a reliance on himself for purposes of adventure, but if you are just starting out, your focus should be on efficient use of your other gear, not on building large fires. If your other gear is properly selected, your choice of axe or saw will not matter much, and you will have plenty of time to experiment with different ones and see what suits you best.

For a more detailed look at what choices I have made when it comes to this other gear, you can see this post:

Everything else, you will learn along the way, and figure out what you need and don’t need. You will gradually learn not to get in your sleeping bag with wet clothing, to keep your compass close to your body so that the liquid does not form bubbles, to select food you can eat without taking off your gloves, and to keep your batteries in your sleeping bag so that they do not die. That however takes time. The things I have listed above, I believe are sufficient to start you out winter camping. Use your common sense, be careful, and do things gradually. Most importantly, do not let fear force you into drastic alterations to the way you camp. You should still be able to travel the same way you did during the rest of the year, carrying your gear on your back, and reaching the places you want to see.

![012[3] 012[3]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgP2UyV_rOevne49jC64TKvo1QFtDg0VqP-vf3K65ZhUb6KcsRaXrHJ-D4yh3KfBUlAfoV5K8rAMasjTWphTQQ03eFl3jHYRC2pqA0e9t_AILzElU8Glys5PNh3piXOY_IDb4eO7oCmk4M/?imgmax=800)

![006 - Copy[3] 006 - Copy[3]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEghRu111BVlVrbwNiWAWb4nYP3M8-UqjJSHs7gzea65TvldG8ij8k4ufFmIxQIs_ittKTiJnwXdZBgdH6DHydqiI0_7PyjOxOlFv3XOA7sVSN2-_rs6lNa_z9jKfZD9dMk1BE7hyphenhypheny6LwHw/?imgmax=800)