Previously I posted about some basic leather working gear which would allow you to complete a few projects. You can find the post on the low cost kit here, and on the intermediate kit here. For this particular project I will be using the items in the intermediate kit, but it can also be done with just the low cost kit.

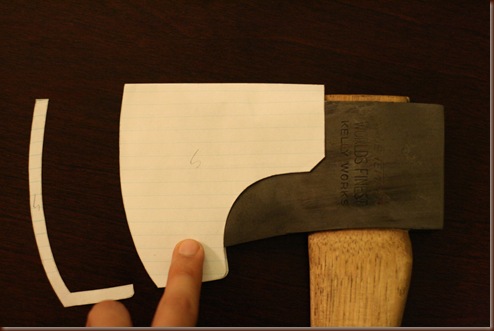

The first step when making a leather axe sheath is to create the template. This is probably the hardest part of the process. Take a piece of paper, place the axe head on it, and start designing the sheath. Keep in mind the sheath has to be large enough to allow for stitching around the axe head, while still giving it room to move in and out. For this particular kind of sheath, I also use an insert where the two sides of the sheath meet. This creates a stop for the blade, so it does not cut through the stitching. You will have to make a template for that insert as well.

When you cut out your template, fold it over the axe head and see if it fits, leaving enough room for stitching. Keep in mind that leather is thicker than the paper. When you fold it over the axe head, some of the length will be eaten up in that fold (much more so than with the thinner paper). You will have to compensate for that by leaving the paper template a little longer on the end opposite where the you are making the fold.

Now trace out the prepared templates on to a piece of leather and cut them out using a pair of scissors.

Now using some leather glue, fold over the sides of the sheath into place, put the insert along the edges in between the fold, and glue the assembly. A set of small clamps makes this step a lot easier.

After an hour the glue should by dry, and you should have the general outline of the sheath. Test it on the axe head and make sure it fits before you do any further work with it.

If it fits, take your stitch groover, and make a groove along the edge of the sheath where you just glued the two pieces along with the insert. Make sure the groove aligns about the middle of the insert (if your insert is a quarter of an inch wide, make the groove an eight of an inch from the edge of the sheath).

Then take your overstitch wheel and mark the stitch holes within the groove that you just made.

Now take your awl and make the holes that you just outlined. The holes should be of good size so you can easily pass a thick needle through them.

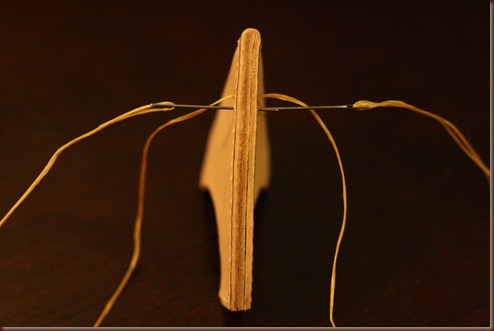

Now take a length of artificial sinew (or any other cordage you line) and thread a needle through each end.

Thread the cordage through a hole at one of the ends of the sheath, until the center of the cordage is in the hole. Now, pass one of the needles through the next hole, and pass the other needle in that same hole from the other side.

Continue the process until you have completed the stitching. When you reach the last hole, just double back once, and cut off the excess cordage.

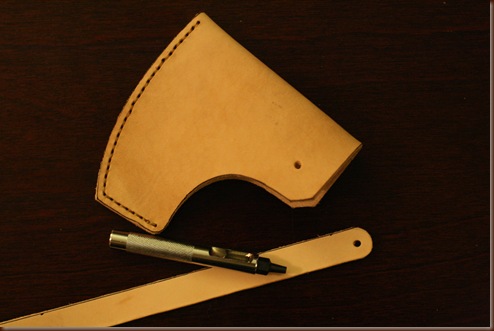

All that is left now is to add the strap that will hold the sheath. Cut out a length of leather to the desired width.

Use a hole punch to make a hole in the locations where the strap will be attached.

Attach one of the strap ends with a tack.

On the other side of the sheath, place the bottom part of the snap.

Now put the sheath on the axe, and measure out the length of the strap.

Make a hole at the desired location and attach the top part of the snap.

Your sheath is now complete. Coat it with some oil for protection.

I’m sure there are better ways to make a sheath, but this is how I make mine. It is a fairly easy process. The hardest part is making the template. The same sheath can be made with the low cost leather working kit simply by using tacks instead of stitching.