Random thoughts on axes, knives, axe use, woodworking, bushcraft, wilderness survival, camping, hiking, and gear review.

Wednesday, December 30, 2015

How to Camp Out, by John M. Gould

Tuesday, December 22, 2015

Trip Report: Beaver Pond Duck Hunting 12/19/15 - 12/20/15

I am definitely not a duck hunter. I just don’t have easy access to the areas where hunting would be much use. If you want a high chance of success when duck or goose hunting, you need either large bodies of water, or open farm fields. That’s where ducks and geese like to land, so you set up decoys, hide in a blind, and try to call in the flocks. Unfortunately I don’t have access to either such terrain. Since I hunt public land, I have no access to farm land, and most decent size bodies of water are too easy to access, and as a result not ideal for the trips I want to do. What I am left with are small ponds in the middle of the woods. I have indeed been lucky in the past and have seen a handful of ducks in some such small ponds, but hunting those areas is really not a productive way to do it. You have to spend the day backpacking to a small beaver pond in the hope that there are two or three ducks there. Sometimes there are, most times there are not. If you are lucky, you then have to stalk the ducks until you are within range, and take the shot. It works, it’s just not a productive way to do it.

Productive or not, my main goal when hunting is to get out into the woods, so this type of hunting is just fine with me. I had a few ponds in mind, and I set out before sunrise.

Monday, December 14, 2015

Venison Jerky Recipe

The usual way to make jerky, and the way I have done it in the past, is to use a food dehydrator. Unfortunately, I threw mine out when I was moving, so for this recipe I had to use the oven.

Ingredients list for 1lb of venison:

- 4 tablespoons of soy souse

- 4 tablespoons of Worcestershire souse

- 1 tablespoon of ketchup

- 1/4 tablespoon of garlic powder

- 1/4 tablespoon of onion powder

- 1/4 tablespoon of crushed black pepper

- 1/2 tablespoon of salt

The first step in making the jerky is to remove all of the fat and connective tissue from the meat. For me this was the most time consuming part as I am not a good butcher. It is however an extremely important part to do right because otherwise the dehydration will not work well – fat does not dehydrate.

Once the meat is cleaned up, slice it into 1/8 inch thick pieces. This is of course easier said than done, especially when you are working with less than ideal cuts. I like to start with the top of the piece of meat, and then keep cutting around like unrolling a roll of toilet paper. That should give you a good size thin piece of meat that you can then cut into strips. If you end up with any thick sections, use the back of the knife to flatten them out.

When the meat is prepared, put it in a large Ziploc bag or a container together with the above ingredients. Make sure to mix well. Leave the meat to marinate in the mixture overnight.

The next day remove the meat from the marinate, drain any liquid that is till on the meat, and place the strips on a baking sheet. Do not overlap any of the pieces. Ideally you would be able to use a rack of some sort for this step, but a baking sheet or pan will work fine as long as you don’t have any liquid (marinate) dripping form the meat or fat that has been left over. At this stage I also added some extra salt to the surface of the meat. Only do that if you like your jerky salty.

Preheat the oven to 170F (77C) and put the soon to be jerky inside. Keep it in the oven for about seven hours. It’s a process that will take a good part of your day. The jerky should be ready within six to eight hours. Since you are not using a rack, for the last hour you may want to flit the pieces of meat around so that both sides dry completely.

And then you should end up with some nice jerky. This past weekend I did about two and a half pound of venison, which from the looks of it is not going to last us very long.

Thursday, December 10, 2015

Video Series Highlight: Ask Paul Kirtley

For quite some time now I have been following the writings of Paul Kirtley, for whom I have great respect as a person and as a woodsman.

For those of you who are not familiar with him, Paul is a UK based bushcraft instructor who runs Frontier Bushcraft. Prior to starting Frontier Bushcraft, Paul was an instructor for Ray Mears and has collaborated with several well known educators in the field. His school has received a number of awards.

In this post I wanted to highlight a series of videos that he is doing called “Ask Paul Kirtley”.

You can see a complete list of episodes here, or you can follow them on Paul’s blog here.

The series is simply based on Paul answering questions that he has received from viewers. The episodes run almost an hour in length, and answer the questions fairly directly and without fluff.

As you guys have probably noticed, I rarely do any endorsements for instructors or schools. In fact, you have probably seen me be critical of most such media personas. There are two reasons why I decided to do this post.

The first reason is that I appreciate it when people take time to put out valuable information without a financial aim in mind. I appreciate that Paul takes time away from teaching classes at his school in order to answer questions people may have without advertising products or trying to drum up attendance at his school.

The second reason is that recently Paul was accused of being the equivalent of an armchair bushcrafter because he released a video that he shot in his office. This of course is a phenomenon familiar to anyone who runs a blog or a YouTube channel; drive-by insults from anonymous individuals is just part of the reality. I bring this up not because anyone is taking those comments seriously, but because I want to give you my opinion on the matter.

It is my opinion that Paul Kirtley is one of very few instructors who I don’t consider armchair woodsmen. In that I include not only online personas, but actual instructors as well. Sadly, most instructors, even the ones who intensively practice wilderness skills, have very limited knowledge of what it is like to be in the wilderness. The reason is that all of their skills are learned, practiced, and taught within ear shot of the house or car. They lack the necessary experience of actually being in the wilderness to put those skills in context. For anyone who has spent any time in the woods, it quickly becomes very obvious who those people are based on the skills they prioritize, and the gear they carry. Paul is one of the few people who actually spends time being in, and traveling through the wilderness, not just in the UK, but across the world. For that reason, while I do not always agree with him, I respect what he ha to say.

So, all that being said, I hope Paul keeps up the series, I hope you guys check it out, and maybe even ask him a few questions.

Wood Trekker does not have any affiliation with Paul Kirtley or Frontier Bushcraft, and I reserve the right to be critical of either as the need dictates. ;)

Thursday, December 3, 2015

The First Solo Unsupported Crossing Of Death Valley

This post is a bit delayed, as the crossing occurred early in November 2015, but I wanted to put some focus on the expedition. Because of my location, I often focus on cold weather achievements, and sometimes overlook expeditions in more arid climates. Well, it’s hard to get more arid than Death Valley.

Between October 30, 2015 and November 7, 2015, Belgian adventurer Louis-Philippe Loncke completed the first solo unsupported crossing of Death Valley.

Loncke covered 150 miles in eight days, exceeding the six days he had planned for the crossing.

Unlike previous attempts, Loncke decided to forego pulling a sled, and instead used only a backpack to carry his supplies.

The expedition was by no means uneventful. A water bladder leak, and an improper salt balance in the water threatened to end the attempt midway, but some ingenuity and luck allowed Loncke to overcome the problem.

You can see the trip journal and more photographs on Louis-Philippe Loncke’s website here.

Monday, November 30, 2015

Solo Stove Lite Kit Review

Last month I was contacted by the manufacturer of a portable wood burning stove called the Solo Stove. They provided me with a stove and pot set free of charge, and I agreed to review it. The stove was their most portable model, the Solo Stove Lite, and the pot was a Solo Stove 900 pot designed for the stove, so that the stove can fully nest in the pot.

First, let’s get the obvious out of the way: this is a Bushbuddy clone. There is no way around that. You are either okay with it, or you are not. That being said, there are some differences to keep in mind. Mainly, the Solo Stove is much more robust. It is made of thicker steel, and the construction is very professional and polished. I never had any fear of crushing the stove, nor did you have any visible weld marks. The construction is something I would expect from a larger manufacturer like MSR. The downside is that it weighs 9 oz, significantly more than the 5 oz Bushbuddy Ultra. On the upside, the cost is correspondingly less, at about $70.00.

The stove measures 4.25 inches in diameter, and 3.8 inches in height (5.7 inches when expanded). It fits perfectly in the provided Solo Pot 900, a 900ml stainless steel pot, both of which come in a good quality stuff sack. The pot weighs 7.8 oz and is 4.7 inches in diameter and 4.5 inches high, and costs about $35.00.

The pot stand portion of the stove flips over and nests within the stove in order to save space. You pull it out and place it upright when you need to use the stove.

The theory behind it is that once you start a fire in the stove, and heat builds up, the additional wood you place in it will not only burn, but gasify. The heat will release combustible gases from the wood, which will then mix with a secondary amount of oxygen and ignite. This should produce a much cleaner and more complete burn.

Even though the combustion is supposed to be cleaner and more complete, it still produces sooth and residue. The wood is burnt fairly completely, leaving mostly ash.

So, this is the stove at a glance. These are the specifications, and the theory behind it. Now, let’s get into the actual discussion of how well it performs as a stove.

Let me start by saying, that the stove works very well for its intended purpose. Once lit, it gasifies beautifully, and you can bring water to a boil with a very small amount of wood. The kit is very portable and easy to set up. The stove is well insulated from the ground, so it leaves no marks when used.

There are however two significant downsides to the stove, not because of the manufacturer or even the specific design, but just by virtue of being a small wood burning stove.

The first downside is that as a non-vented wood burning stove, you can not use it in a tent. For me this is a significant disadvantage to a stove. In bad weather I have to be able to use it inside a tent. For example, when I was testing the stove last week, I found myself in a very exposed and windswept location, where most stoves would have struggled to boil water. If I had a canister, alcohol, or even a while gas stove, I would have used it within my tent, eliminating the problem. With this stove I couldn’t. All stoves pose a danger when used inside a tent, but even with the cleaner burning gasification wood stove, you will be smoked out of your tent in no time.

The second downside is that for all practical purposes, you are carrying 9 oz of gear in order to make a tiny fire. In turn, there are two issues with this. The first is that I can build a relatively small fire without the use of any stove, and save myself the 9 oz, or better yet I can bring 9 oz of fire starting material instead. The second issue is that the smaller of a fire that you try to make, the harder it is to actually build.

If you are making a fire from dry, easily combustible materials like birch or pine, the job is relatively easy: you put some birch bark in the stove, light it, put some small, dry, pine twigs on top, and you have a tiny fire that you can then feed with finger-thick pieces of wood. However, try doing that in an oak and hickory forest. If you are relying on semi-dry grass as tinder and hickory sticks for fuel, starting such a tiny fire can be a nightmare. Woods like oak, hickory, and maple require high heat to burn. In a small space like this stove, where you have a limited amount of poor quality tinder, it can be almost impossible to raise the temperature high enough to ignite such woods. The problem can be overcome by building a larger fire where a sufficient amount of kindling (dry grass, feather sticks, bark, etc) can create enough heat to ignite the wood, but that is not possible in the small confines of the stove.

So, ultimately, my issue with this stove is the same issue that I have with all small wood burning stoves. It is a great design, and works the way it is supposed to. However, when I can more easily build and use a fire without carrying any stove at all, why do I need the stove? Sure, in some cases it is slightly more convenient than a fire, but in many cases it is less convenient. Under less than ideal conditions it is easier to start a large fire than to build one inside a small stove like this one. Under adverse conditions it is difficult to light quickly, and can not be used inside a shelter.

The Solo Stove Lite is a well built and designed tool, and works very well with the 900ml pot as part of a kit. However, you have to take the stove for what it is: a fun tool to use when you are enjoying yourself in the woods. In that respect, it is spectacular. There is just no way for you not to have a smile on your face when you are feeding little sticks into the stove and watching the gasification process.

What the stove is not is a survival stove or a stove for adverse conditions. When you actually have to rely on the stove, especially when you are in a less than ideal spot, this is not the way to go. You need a stove that will work quickly every time, can be operated easily, can work under difficult conditions, and can be used inside a shelter. The Solo Stove is none of those things.

As always, I have very mixed feelings about small wood burning stoves like this one. On one hand it is well made and a lot of fun to use. On the other hand, it occupies a strange space between a backpacking stove and an open fire, and from a practical stand point is no better than either. If I have the desire and the ability to make a fire, then I can just make a small fire; or even a large one if I needed it. If I actually need to rely on a stove because of bad weather, hypothermia, lack of material to burn, etc, then a more conventional backpacking stove (canister, white gas, alcohol, etc) is a much better option. Of course, practicality is not always the controlling factor of what we use in the woods. As long as the limitations of the stove a kept in mind, I think it can be a fun addition to any camping trip.

Saturday, November 28, 2015

Survivorman Season 7: Survivorman Is Back, But Forgot to Tell Anyone

Hey guy, did you know Survivorman is back? Well, he is, but no one would blame you if you had no idea. Season 7 of Survivorman premiered earlier this month, to virtually no promotion.

It has been airing on The Science Channel (Discovery Science) at 10pm Eastern on Saturdays. So far three episodes have aired:

- Episode 1: Fan Challenge (November 7, 2015)

- Episode 2: Transylvania Part 1 (November 14, 2015)

- Episode 3: Transylvania Part 2 (November 21, 2015)

I’ve been shocked by how little promotion the show has seen. Not only is it not shown on more mainstream cable networks like The Discovery Channel, being relegated to its less popular Science Channel, but there was almost no advertisement. In October I saw some promos on The Science Channel about a new season, but when I checked Les Stroud’s website, there was nothing about it. The last season listed was the silly Bigfoot chase Season 6.

Being honest, Survivorman was never a show with big ratings. It can simply never manufacture the level of drama other survival shows pull of for purposes of ratings. Even in the early days it was being soundly beaten by the Bear Grylls fiasco Man vs. Wild. I imagine him spending a season chasing after Bogfoot didn’t do much for the appeal of the show either. I know I skipped that season.

This new season has followed the usual pattern. It is informative in a subdued, realistic way. The first episode showed him surviving along with a fan, with Les giving him some tips. The second and third episode showed him getting lost in Transylvania. For those of us who have been in similar situations, the episodes can be interesting, but generally they are relatively slow moving.

If you are a Survivorman fan, you can still catch the rest of the season. Again, it airs Saturdays at 10pm on The Science Channel.

Monday, November 23, 2015

Trip Report: Opening Days of Deer Season 11/21/15 – 11/22/15

I usually try to keep the trip reports to one per month at most because I know they can get boring, but this month I figured I would do a second one because this past weekend was the opening of deer season where I am.

I haven’t had any luck with deer hunting the past two years, so for this year I decided to make a change. The first change was to hunt in an area that didn’t have antler restrictions. That would immediately improve my chances. I wouldn’t be able to rely on calls as much, but the number of animals I could take would be greater.

The second change was to follow a tip I read from Steven Rinella in his book The Complete Guide to Hunting, Butchering, and Cooking Wild Game: Volume 1: Big Game. The book itself is very well written and illustrated, and I highly recommend it. It doesn’t contain anything ground braking, but it has many excellent tips. Well, one of the chapters was on public land hunting, and what I got from it was that when hunting on public land you have to not only understand the behavior of the animal you are hunting, but also of the hunters who are hunting the are with you and how that interacts with the fame.

Keeping that tip in mind, I decided to change my strategy this year. Instead of hunting the low lands where deer like to be this time of year, I decided to do the opposite. I found the area most distant from any place that was easily accessible to hunters, and in that area I located the highest, most inaccessible point. My theory was that even though deer wouldn’t like such terrain, all of the hunters who tend to hunt close to roads and on the easy terrain, would push the game deeper into the woods and higher in elevation towards me.

So I got to the forest about half an hour before sunrise and set out. It would be a long trek to the area on the map that I had picked out so I wanted to get a head start.

Once it was officially sunrise (the legal time to start hunting), I loaded the rifle and kept it at the ready just in case I spotted a deer on my way into the woods.

I spent a good portion of the day backpacking in. I heard several shots from areas that I had already passed. I kept going in the hopes that those hunters would push the game to my chosen destination.

I didn’t encounter any game along the way, and when the sun started going down I set up camp near the location where I had planned to hunt.

Even though I was in a pretty exposed location, the wind wasn’t nearly as bad as last weekend. Overnight temperatures were about 20F (-7C). I was again using my three season bag, but I had my thick coat with me, so I slept in it and was fine. In the morning I again got up about half hour before sunrise, packed up, and set up on a ridge I had located the previous day, overlooking two intersecting ravines.

I waited for about two hours. Shortly after 8 am I spotted two doe making their way through one of the ravines. I was surprised that they weren’t aware of me because the wind was not in my favor in the direction from which they were coming, but they didn’t spot me. I was using Nose Jammer scent blocker, which I had sprayed the previous day. Maybe that’s what made the difference. I don’t know.

I positioned myself and took a shot from the knee at the lead doe at about 50 yards. I used my Savage 11-111 F rifle in .308 with a Nikon Prostaff 3-9x40 scope, which I have zeroed in at 50 yards. She rushed for about 20 feet and then dropped. I cleared the rifle, waited a few minutes to make sure she was dead, and then made my way down into the ravine.

It was a fully grown doe, about 150lb. I took it with a lung shot. Even though the entry point was the neck, it wasn’t a pure neck shot because I was up and in front of the deer. The bullet entered the neck and then continued down and back through the lungs, stopping in the far shoulder blade.

Now it was time for the hard work. I had to skin, butcher, and carry out the deer. I debated with myself about whether or not to gut it or to just bone it out without gutting, but ultimately decided to gut it so I can get the heart and liver.

All the processing work was done with my Mark Hill Mora #2 custom clone and a Bahco Laplander saw. The saw is obviously not great with bone because it’s too aggressive, but it got the job of cutting through the sternum and pelvis done. The knife performed beautifully. I know many hunters prefer the Havalon style blades, but I like a less delicate tool. I’ve been very impressed with the Mark Hill knife. I processed the whole deer with it without having to touch it up. When I was done I spent a minute on the fine side of my DC3 sharpening stone and it was shaving sharp again.

After I gutted it, I skinned it, and removed the meat from the bones. I packed it all in a T.A.G. game bag. The T.A.G. B.O.M.B. kit which I was using comes with several game bags, but they are large, and I only needed one. The kit was developed for elk hunters, so it was oversized for my needs.

I figured I would spare you the rest of the process. I placed the game bag in a plastic trash bag and transferred the tag to it. For those who don’t hunt, game bags are designed to keep insects away from the meet and allow it to breathe and cool off. They will let blood go through, so if you want your backpack to stay clean, you have to put them in a plastic bag. I am not a skilled butcher, so the process took me over an hour.

When I was done, I cleaned up, packed up all of the meet in my old Gregory Palisade 80 pack, and started making my way back.

It took me many very long hours to make it out of the woods. I’ll have to figure out a good way to attack the rifle to my pack, so that I can use my trekking poles. They would have really helped.

Overall, everything came together nicely. My strategy worked, all of the gear performed well, and I didn’t have any difficulties. It would have been nice to spend an extra day in the woods and cook up some of the meat, but I wanted to get home as soon as possible to make sure I can preserve all of it.

Tuesday, November 17, 2015

Trip Report: Bailey Cemetery 11/14/15 – 11/15/15

It’s still a week before deer season opens around here, so I decided that while waiting I would just go and relax in the woods. After some searching over the maps, I noticed that there was a marking for an old cemetery in the northern section of Harriman State Park. I figured I would make a trip out of it and make my way to it.

The weather was brisk, around 40F (4C), and very windy. It still wasn’t bad for mid November.

Rhea came along for the ride. In fact the reason why I picked this part of the woods is because there is no hunting here and I could bring here safely.

I took the long way to my destination so I could pass by an old mine. Back in the 18th and early 19th century, in these forests there were a number of small villages and homesteads that were eventually abandoned. Sometimes you can see the remnants of house foundations, but the best preserved evidence of their existence is the small cemeteries and iron mines cut into the rock.

The mines are usually very shallow, going about a dozen feet into the rock. They were cut with hand tools, and followed the iron ore veins running on the surface.

From there it was a steep climb up the mountain. One of the frustrating things about Harriman State Park is that there are limits on where you can overnight. There are “shelter” locations dispersed through the mountain, and you have to set up within a certain distance from them. This is done to decrease the overall impact on the forest, and it has the added benefit of limiting the number of people overnighting in the forest. You can’t just walk 100 yards into the woods and set up a huge camp. If you want to spend the night, you have to walk in at lest good five miles, which requires some commitment.

The down side is that you can’t chose your location based on the weather conditions. These shelter sites, which are no more than a makeshift leanto, are usually set up in locations with nice views, which in turn are usually on top of mountains. That is great during summer, but in adverse weather, such as this past weekend, where the winds were extremely strong, setting up in such a location is far from ideal. This is the shelter I encountered when I got to the top of the mountain; a leanto on a rock outcrop:

I never use the leantos. It never appealed to me, and besides, there are people who rely on them, especially some through-hikers, so I usually go as far away from them as I can under the regulations (usually about 100 yards), and set up my camp. In this instance, that left me exposed to some pretty severe winds.

I haven’t had to fight winds this strong in a long time. They were strong enough that even with my four season tent, it wouldn’t stay up unless I pitched it directly into the wind. Even then, several times during the night I had to get up and put my body against the tent wall to keep it from collapsing when wind directions changed.

After I pitched the tent and secured it, my next challenge was to cook dinner. For this weekend I was testing a small wood burning stove called the Solo Stove. I was asked to test it by the manufacturer, so I’ve been trying to get some use out of it. For all practical purposes, it is a Bush Buddy clone.

The first problem was the wind. It was so strong that cooking in it without a stove specifically designed for the purpose, like an MSR Reactor, would be extremely difficult. The wind just sucks the heat out of the stove. Ordinarily, under such conditions I would just cook inside the tent. Unfortunately you can’t do that with a stove like this one. So, I found a somewhat sheltered spot near some rocks, and gave it a try.

The second problem was that such small wood burning stoves rely on your ability to make a fire, and having the resources to do it. It is relatively easy to do if you were in an area abundant in birch and pine trees. You can easily make a small fire within the stove with such woods. However, where I was there wasn’t a single birch or soft wood in sight. All I had was hickory, oak, and maple. For tinder all I had was grass. Hickory, oak, and maple make great fuel woods because of their extended burn time. However, they are very difficult to light. They require a lot of heat to get going, even when they are processed into small pieces. The usual solution is to build a larger fire set up. You use a good bundle of grass to get the fire going, you surround it with thin pieces of wood, and then larger ones. Ones the grass start burning, the wood around it traps the heat, and eventually the ignites the wood and reaches sustainability. Doing that is a tiny stove however, is extremely difficult. You just can’t place enough tinder (grass) to raise the heat high enough to light the wood you are using.

Long story short, it took me nearly an hour to get the stove working and somewhat warm up some water (the wind wouldn’t allow more than that).

The night was pretty cold. I had with me my three season bag, and I was cold. The wind was relentless all night, and had to get up several times to secure the tent.

In the morning I got up early and headed down the other side of the mountain. It was an easy hike to the cemetery that I was looking for. There were no trails leading to it, but there were some unmarked paths. The cemetery was easy to spot this time of year. It was surrounded by the remnants of a low stone wall.

Some of the grave stones were toppled over. Most of them had the name Bailey on them. That’s why I am referring to it as the Bailey cemetery. This is pretty common in this area. There were many small villages and homesteads, at time composed only of one family.

All of the grave stones were from the 1800s. The one above shows the realities of life back then, marking the grave of two and a half year old child.

On that somber note, I made my way back, going around the mountain, and out of the forest. It was a good weekend to test the gear against some strong winds. Everything worked out well, and it was a lot of fun.

Thursday, November 5, 2015

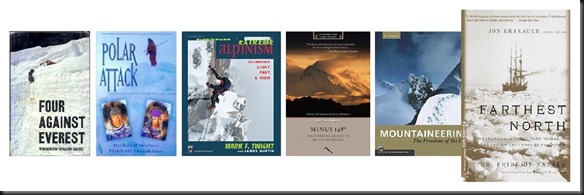

My Favorite Cold Weather Exploration Books

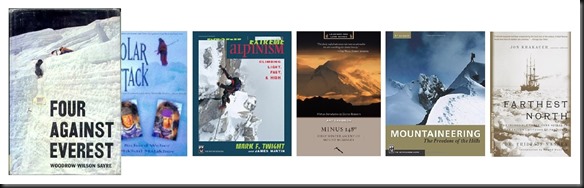

Winter is just around the corner, and and my mind has been drifting towards undertaking different, foolish, cold weather adventures. When I am in such a mood, I often go back to books on the subject that I find both inspirational as well as educational. There are a few books which chronicle journeys of cold weather exploration, which hold a prominent place on my book shelves. In this post I wanted to share that short list with you in the case you were looking for some reading. The books are listed in no particular order.

Four Against Everest by Woodrow Wilson Sayre, 1964

The first book on the list is Four Against Everest by Woodrow Wilson Sayre. It chronicles the 1962 attempt at a summit of Mt. Everest by a team of four men, Woodrow Wilson Sayre, Norman Hanseng, Roger Hart, and Hans-Peter Duttle. This American-Swiss team of amateurs managed to get to within 3500 ft from the summit before having to turn back. They did it while climbing without Sherpas, without permits, and without oxygen.

The book does an excellent job documenting the attempt, complete with gear lists and food rations data. It is full of useful advise, even though it was written decades ago. Not only does this book foreshadow more modern mountaineering approaches, but that approach of climbing as a self contained unit, without huge expedition and support teams, really strikes a cord with me.

Polar Attack: From Canada to the North Pole, and Back by Richard Weber and Mikhail Malakhov, 1996

Polar Attack follows the accounts of Richard Weber and Mikhail Malakhov, documenting their 1994 failed attempt at an unsupported round trip journey to the north pole and their 1995 successful trip, making them the first people to complete the task.

Even though the chapters of the book alternate as one is written by Weber and the next my Malakhov, which gives it the feel of a compilation of journal entries, it flows very well and presents the material in an educational yet exciting manner. The accounts of both attempts are filled with valuable information that can only be gained under such conditions.

Extreme Alpinism: Climbing Light, Fast, and High by Mark F. Twight and James Martin, 1999

It is hard to imagine that one of the most influential books when it comes to cold weather climbing, and I would say to cold weather expeditions in general, is now over a decade old.

When I first started reading the book, I expected it to be very technical in nature. In many respect it is, doing a fantastic job of describing different systems and techniques. Surprisingly however, the book also contains many personal accounts of different expeditions, which really transform the book from a technical manual into more of an exciting read.

Minus 148 Degrees: The First Winter Ascent of Mount McKinley by Art Davidson, 1969

In many ways Minus 148 Degrees reminds me of the book Four Against Everest you see further up the list. The goal of the expedition is just as far fetched, and the team is similarly foolhardy and as a result the achievement inspiring. The book is an account of the first winter ascent of Mt. McKinley (Denali) in 1967. The feat was accomplished by a team of eight men, of which only seven returned. The name of the book stems from the temperature recorded by the team as they were caught by a six day blizzard on their descend from the mountain.

The book is not a technical how-to. If anything, it is the opposite, chronicling different mistakes made by the team. Many would call the expedition reckless, but for some reason I find it very inspirational. I suppose that is because it demonstrates how far a small group with little support can go through determination and grit.

Mountaineering: Freedom of the Hills, 8th Edition, originally published in 1960

Originally published in 1960, Mountaineering: Freedom of the Hills is now in its 8th edition, featuring updated content. The book is a technical manual that covers the basics of mountaineering and cold weather travel. It is the book that just about anyone interest in the subject starts with, and rightfully so. It is well written, contains tons of very useful information, and is easily accessible.

Farthest North Vol I and Vol II by Fridtjof Nansen, 1897

For my last pick, I am going way back, to one of the greatest cold weather explorers in history, Fridtjof Nansen. In particular I would recommend Farthest North, which chronicles in detail the 1893 Fram expedition, which attempted to reach the north pole. The First Crossing of Greenland also by Nansen, describing his crossing of Greenland was a close contender.

The book comes in two volumes. The first volume details Nansen’s preparations for the expedition and the time spent drifting with Fram (the name of the ship). Unlike many of the expeditions featured in the books further up on the list, this is an example of large scale, well funded expedition. Far from being a group of guys who just decided to go on an adventure, this is an expedition for national pride; well funded and well planned. As a result, I personally found the first volume to be rather boring at times. While the journey is brilliant, my interests are not in sailing or expedition logistics.

The second volume focuses on the time spent by Nansen and Hjalmar Johansen attempting to reach the pole by skis. They were forced to turn back, undertaking a year long journey over the polar ice, heading south towards safety. The account, composed of their journal entries is mind blowing. If for no other reason, the book is worth reading so one can get the idea of how amazing these men really were.

The two volumes are in the public domain and can be downloaded for free: Vol I, Vol II. The First Crossing of Greenland is also available for free download here along with other locations online.

So, these are just some of my favorites. For one reason or another I like reading them. What about you guys? What are some of your favorites?

Thursday, October 29, 2015

Fire and The Modern Woodsman

Some time ago I started writing about a concept I called The Modern Woodsman. The idea itself was nothing new, but I felt that it needed to be reiterated and it’s existence pointed out. In short this is the concept that woodsmanship did not die out or vanish after some “golden age” decades ago. Instead it asserts that woodsmanship continues to exist, develop, and evolve through every generation including ours. Modern woodsmen continue to travel through the wilderness, using techniques learned from past generations as well as the developments in knowledge and technology that have come since then.

The Modern Woodsman: an individual who is able to undertake long term, long distance trips, deep into the wilderness, only with supplies one could carry and what could be gathered from the surrounding environment. The equipment and skills used are guided by their actual practicality and are not restricted by any historical period limitations or aesthetic factors. The trips undertaken occur in the present, within the context of our current society, laws, and regulations.

In this post I want to look at fire and fire making methods within the context of The Modern Woodsman.

When discussing fire and modern woodsmanship, most would expect a discussion on the tools used for fire starting, and whether one should use new ones or ones from the past. While there is certainly fire starting technology for us to look at, I want to start with a much more important concept when it comes to fire. I want to start with the significance fire has to the modern woodsman and how that differs from the role it has played for earlier generations of woodsmen.

The Woodsman’s Reliance on Fire

If one looks only at the developments in fire lighting technology, one may conclude that we have simply had changes in the degree of the ease of fire lighting; friction fire lighting methods get replaced with fling and steel, then with matches, then with lighters, etc. However, I believe that a much more important shift in kind has occurred for the modern woodsman and his relationship with fire that goes far beyond its method of lighting; a result of the overall progression of technology utilized by the woodsman.

Vague enough for you? Well, what I am trying to say is that developments in the overall gear of the modern woodsman have significantly decreased the importance of fire to the woodsman. I believe that change has been a radical shift when compared to the relationship between fire and earlier generations of woodsmen.

Reading the accounts of woodsmen from the early 20th century and prior, we get a clear picture of how fire was an essential tool for being in the woods. It wasn’t a nicety, or an emergency measure, it was a necessary part of every day existence in the wilderness. Keeping one’s self from freezing to death, purifying water (although admittedly most didn’t seem to care), cooking food, etc all depended on the existence of a fire. As a result, many of the tools carried by woodsmen of the time were designed to accommodate that need.

This relationship with fire for our predecessors was a necessity dictated by the available overall technology that was at the woodsmen’s disposal. A blanket and a canvas tarp are very poor protection from the elements, and one wouldn’t last long without a good fire. Water filters and portable stoves were non existent. On the flip side, there were virtually no regulations limiting the number of trees you can fell in a day or where you can light a fire.

At some point however there was a drastic shift in the relationship woodsmen have with fire; a change in kind, not just in degree. Fire went from being a necessity to being a nicety. It stopped being essential for everyday life in the woods. Instead it became something to be relied on in emergency situations, and a source of entertainment and comfort during long nights.

I believe this change has been a direct result of developments in outdoor technology. Just like the tent/tarp allowed woodsmen to cut the connection to natural shelters and venture into otherwise unprotected areas, other technological developments have severed the woodsman’s need to rely on a fire. Modern sleeping bags easily allow a woodsman to spend many nights in the woods in extremely low temperatures without reliance on a fire. Similarly, highly insulative yet portable clothing has allowed travel without having to stop and warm one’s self by a fire. I believe these were the most significant changes which have altered the relationship the modern woodsman has to fire. They are then followed by other changes like the availability of portable water filters, and convenient lightweight stoves.

Moving beyond the technology, the modern woodsman has also had to make changes in his reliance on fire due to legal considerations and overall ecological responsibility. We all understand that at certain times of the year in certain places it is not a good idea to start fires, whether or not regulations dictate so. Similarly, we understand that felling a fully grown tree each day so we can keep a fire burning through the night is not the most ecologically sound approach in many parts of the world.

The result of all this has been that the modern woodsman has a very different relationship to fire than previous generations. The shift is much more profound than the type of device one uses to light their fire. In my opinion it has drastically changed how a woodsman interacts with the environment, and is markedly different from the reality faced by prior generations.

Being well versed in fire lighting techniques and being able to build and maintain a fire are still crucial skills for a well rounded modern woodsman. However, the modern woodsman also understands that he is not constrained by the need for a fire, and knows how to spend prolonged periods of time in the woods without reliance on one.

Fire Related Tools

For me a much less important aspect of fire and The Modern Woodsman is the tools related to fire making. Clearly the tools have changed and evolved over the decades, but I believe those changes to be secondary to the above discussion. They are simply a linear improvement of fire lighting technology making the process easier without altering it fundamentally.

That being said, there have indeed been changes. Some of them have been simply the result of new technology becoming available, others have been the result of the decreased reliance on fire discussed above.

Again, at this point you probably expect me to discuss lighters and ferro rods, a favorite online topic, but I believe these technological changes are the least important ones.

- Axe:

A much more significant change that I see is the drastically reduced reliance on the axe. The relationship between the modern woodsman and the axe has altered just as drastically as the relationship to fire, and in large part because of it. For woodsmen of earlier times, who had no choice but to rely on fire during their travels in the wilderness, the axe was probably the most important tool they carried. Each book written at the time dedicated large portions or even full chapters to the topic of the proper axe. The significance of the axe was a direct result of the reliance on fire. An account by E.H. Kreps states: “Only a single blanket and a small, light canvas shelter can be taken and to sleep without a fire under such conditions is out of the question. A good hot fire must be kept going and such a fire will consume nearly half a cord of wood during the long northern night.” Of course he is talking about extreme cold, and is discussing the use of soft woods like pine, but no matter the wood, very large quantities were needed to sustain life in the woods. Without a good axe, the task of gathering that much wood would have been out of the question.

Of course, that is no longer the case; not because an axe is not a good wood processing tool, but because the reduced reliance on a fire, has reduced or even completely eliminated the need for an axe when it comes to The Modern Woodsman. Now, you guys know I am a huge fan of axes. I enjoy working on them and I enjoy using them. The reality for the modern woodsman however is that in most cases the tool in no longer needed, and it certainly doesn’t carry the same significance that it once did. Most modern woodsmen traverse great distances, spend extended time in the woods, reach previously unthinkable destinations without relying on an axe. I think this has been one of the most significant technological changes that has resulted from the altered relationship between fire and the modern woodsmen. We still carry axes because they are fun and because they are nice to have, but much like the need for a fire, it is a nicety. Forgetting your axe no longer spells the end of a trip.

- Stove

The second big technological change when it comes to The Modern Woodsman and fire has been the introduction of the portable stove. While different attempts at such a technology had been made for years, I believe the introduction of the Primus stove in 1892 and its subsequent proliferation has been a very impactful event in woodsmanship. The reason for the impact is not that the stove has replaced the fire as a means of cooking. While practically that has largely been the case when it comes to wilderness excursions, I do not believe that was a driving force for its creation nor the reason for its impact.

What the portable stove has managed to do is to give the modern woodsman a significantly expanded range into terrain that was previously unattainable. Portable stoves have allowed for the exploration of both poles as well as some of the highest peaks. They have taken ancient northern technologies that relied on the burning of fuels like seal oil, and transformed them into a portable source of fire, not reliant on wood. It’s main benefits interestingly are not warmth, or even the ability to cook, but rather the ability to melt snow and ice into water. Without this technology, many areas of the world would be much harder or outright impossible to reach.

While the main practical impact of the stove to the modern woodsman has been the exploration of harsh regions, its impact has spread far and wide, and has had an unquestionable impact on fire as used by woodsmen around the world. Under many circumstances, it has eliminated the need for a fire (or more precisely, has made it portable and self sustained), even further distancing us from the connection prior generations of woodsmen had to it. In many ways that has allowed the modern woodsman to travel faster, further, and into harsh terrain more than ever before. It has also allowed the modern woodsman to deal with exploration of regions where legal or ecological restrictions prevent the traditional use of fire.

- Fire Lighting Tools

Lastly, I want to mention the thing which most people immediately jump to when discussing woodsmanship and fire: the fire lighting tools. Most woodsman strive to have a well rounded knowledge of fire lighting methods. Some are more rounded than others depending on their interest in history. However, the modern woodsman has at his/her disposal very practical and proven tools for lighting a fire. The main ones in chronological order are matches, lighters, and ferro rods. While many don’t realize that ferro rods are a modern tool, they are in fact one of the last fire lighting tools to come on the market. This relationship between woodsmen and fire lighting tools, and in particular the desire to have the most efficient fire lighting equipment can be seen going back to the early 20th century and even earlier. There is a reason the pioneers relied on flint and steel rather than friction fires, and there is a reason everyone from Nessmuk to Kephart used matches. It is the same reason why modern woodsmen use lighters. While each is a finite resource, the capability they offer to quickly and reliably make a fire makes them invaluable to the woodsman.

While much has been written about which exact fire lighting tool one should carry, I believe ultimately it is of little significance. From the perspective of The Modern Woodsman, where practicality on excursions of non-imaginary duration are key, in my opinion the top contenders are lighters and matches. Regardless of your choice however, I believe that its importance is far secondary to the understanding of the new type of relationship that woodsmen of today have with fire, and how as a result approaches described by woodsmen of the past may not be directly applicable.

Studying texts from people like E.H. Kreps and Kephart is important and furthers our knowledge, but we have to be careful when applying their gear lists and techniques to our own, especially when it comes to fire. Much of what woodsmen like them have written on the subject has been due to necessity dictated by the fact that they didn’t have a four season tent and a –40F/C sleeping bag. I doubt Kreps would have been dedicating a part of his day to collecting half a cord of wood for each night instead of checking his traps if he had the gear the modern woodsman has at his/her disposal.

Monday, October 12, 2015

Trip Report: Out For Squirrels 10/10/15 – 10/11/15

I know it’s been some time since I posted, but not to worry. I’ve been getting out and doing the usual trips, I just haven’t had time to write any posts because I’ve been busy with house stuff. Here is one from my last trip this weekend:

I figured I would go out and see if I can get a few squirrels. I’ll hopefully do some pheasant hunting next weekend, but I had nothing planned for this one, so I figured, why not. As I was leaving in the morning however, Rhea was looking at me all excited. She knows that when I put my backpacking clothes on, it’s woods time. So, at the last minute I decided to take her. At that point the hunting became only theoretical with her bouncing all over the forest.

It turned out that the dog wasn’t as big of a problem as I expected. She didn’t cause much commotion. Unfortunately though, I didn’t have the right strategy for getting at the squirrels, and I’m not really sure what to do about it.

The problem was that the canopy was so thick, that even though I spotted a fair number of squirrels, by the time I shouldered my rifle, I would have lost sight of them and was unable to reacquire. The few times where I could still see them, I didn’t have a clear shot. Those of you who know more about squirrel hunting, what do you do in such situations?

Anyway, I had a hard time with the squirrels, but the mushrooms were everywhere.

Hey! You’re not a mushroom. Get out of here!

After all those mushrooms, it was time to set up camp for the evening. I was thinking of starting a fire because I find that the squirrels really don’t care, but I know there were possibly people out deer hunting (it’s too early for rifle season, but bow and muzzleloader are open), so I decided against it. The last thing I want to do is mess up someone’s hunt. So, we just ate and went to sleep.

The night was cold. It came down to close to freezing. I was chilly at times. I woke up early, and made my way out of the forest.

Clearly hunting is not my thing, but I’ll take any excuse to get out into the forest.

![IMG_0969[3] IMG_0969[3]](http://lh3.googleusercontent.com/-ZfmK0wDxSIw/VjIO19rtmbI/AAAAAAAAQFI/PzZtxwjoDvY/IMG_09693_thumb1.jpg?imgmax=800)