This past year I started getting more interested in fly fishing as well as fishing in general. I’m not the type of guy who stays awake at night thinking about fishing, so my needs are simple. After some research I put together a spinning set up that I can easily carry into the woods, and I have been happy with it. Fly fishing however has been a bit more complicated. As a beginner, I have found it difficult to get good information on the subject. Almost all perspectives that I saw were absurdly bias towards one or other of the methods, to a degree where they seemed like bad infomercials… “Has this ever happened to you?!…Then buy our product!”… with the only answer coming to mind being “No! This has never happened to me, because I’m not an idiot!”

The main division, at least from the view point of someone who is new to the activity is between western fly fishing and tenkara fly fishing. Choosing which way to go when purchasing a first rod and fly fishing set up has been difficult.

From what I have been able to see, people’s views on any form of fly fishing are a dubious mixture of about 1/3 facts, 1/3 mysticism, and 1/3 fascination with the exotic. I found it very difficult to get straight answers from anyone who subscribed to a particular form of fly fishing. All the answers seemed light on facts and heavy on concepts of art, spirituality, purity of form, etc. Listening to someone justify why they tenkara fly fish, or fly fish with a western set up, is like listening to someone read from a sales catalog for a particular brand, or worse, as an orientation session for a monastery. As a simpleton, whose interest in fishing begins and ends with catching fish, none of the answers were particularly satisfying for me. As such, I figured I would share with you what I have been able to find and experience over the last year before I too get “spiritually” involved in any particular type of fly fishing and lose perspective.

The first hurdle in finding any factual information about either style of fishing is actually figuring out what the style of fishing entails. It sounds like it should be simple, but it’s not. Once you move past the obvious, that western fly fishing set ups use a reel, while tenkara fly fishing set ups do not, the rest is not that clear. Many statements are made about what is required for western fly fishing and for tenakra fly fishing, but none of it seems to stand up to closer scrutiny. For this post, in order to get some perspective on the two forms of fishing, I figured I would find out a bit more about their history and evolution. As with all my posts that involve history, this is just a quick overview based on information I have been able to find. Do not take it as the definitive guide to the history of the activity.

Western Fly Fishing:

Western fly fishing, or commonly referred to as just fly fishing is defined as “a method of fishing in which an artificial fly is cast by use of a fly rod, a reel, and a relatively heavy oiled or treated line.” Merriam-Webster Dictionary. At its very core, fly fishing is a form of fishing using an artificial fly as a lure. Western fly fishing can then be further delineated to reflect the use of a rod, reel and fly line to cast that artificial fly. None of this however popped into existence in a vacuum.

The first clearly recorded instance of fly fishing is that by the Roman author Ælian circa 200 A.D. in his work Ælian’s Natural History. In there he describes a method of fishing seen in Macedonia:

“I have heard and can tell of a way of catching fish in Macedonia, and it is this. Between Beroea and Thessalonica there flows a river called the Astraeus. Now there are in it fishes of a speckled hue, but what the natives call them, it is better to enquire of the Macedonians. Now these fish feed upon the flies of the country which flit about the river and which are quite unlike flies elsewhere; they do not look like wasps, nor could one fairly describe this creature as comparable in shape with what are called Anthêdones (bumble-bees), nor even with actual honey-bees, although they possess a distinctive feature of each of the aforesaid insects. Thus, they have the audacity of the fly; you might say they are the size of a bumble-bee, but their colour imitates that of a wasp, and they buzz like a honeybee. All the natives call them Hippurus. These flies settle on the stream and seek the food that they like; they cannot however escape the observation of the fishes that swim below. So when a fish observes a Hippurus on the surface it swims up noiselessly under water for fear of disturbing the surface and to avoid scaring its prey. Then when close at hand in the fly's shadow it opens its jaws and swallows the fly, just as a wolf snatches a sheep from the flock, or as an eagle seizes a goose from the farmyard. Having done this it plunges beneath the ripple. Now although fishermen know of these happenings, they do not in fact make any use of these flies as baits for fish, because if the human hand touches them it destroys the natural bloom; their wings wither and the fish refuse to eat them, and for that reason will not go near them, because by some mysterious instinct they detest flies that have been caught. And so with the skill of anglers the men circumvent the fish by the following artful contrivance. They wrap the hook in scarlet wool, and to the wool they attach two feathers that grow beneath a cock's wattles and are the colour of wax. The fishing-rod is six feet long, and so is the line. So they let down this lure, and the fish attracted and excited by the colour, comes to meet it, and fancying from the beauty of the sight that he is going to have a wonderful banquet, opens wide his mouth, is entangled with the hook, and gains a bitter feast, for he is caught.” Aelian On Animals, Vol XV, 1. Loeb Classical Library, Harvard University Press (1972) p 203-4.

In short, Ælian describes a method of fishing where an artificial fly is tied to a six foot line, which in turn is tied to a six foot rod, and then the fly is presented to the fish either by casting or lowering down to the surface of the water.

There are sporadic references to fly fishing after that period, but no complete text on the matter until the publication of Treatyse of Fysshynge With an Angle as part of The Boke of St. Albans in 1496. The writing is often attributed to Dame Juliana Berners, but not confirmed.

The text is not the easiest to dead, but they say a picture says a thousand words. The above picture should give you a good idea of the set up. The book gives instruction on construction of a rod, a line made form braided horse fair, and it gives direction from twelve artificial flies, two for each month from March till August.

While the technique for producing the equipment is better outlines, and the rods seems to exceed twelve feet, the method appears to be very similar to that described by Ælian circa 200 A.D.

That starts to change in the 17th century with the publication of The Complete Angler by Izaac Walton in 1653. Other writers from that same time, including Charles Cotton, who wrote a chapter on fly fishing in the fifth addition of The Complete Angler, Thomas Barker who wrote Barker's Delight or The Art of Angling in 1659, and Colonel Robert Venables who published The Experienc'd Angler in 1662.

The tools and methods remained much the same. Rods lengths were extended, at times up to eighteen feet. The line was still made of horse hair, now twisted, tapering so that it thins out towards the front of the line (down to three horse hairs). While lines were most often tied to the tip of the rod, there are some references about anglers leaving the line untied and simply threading it through a loop at the tip of the rod, controlling the extra line with their left hand. That made the floating of the line downstream for considerable distances possible. “The typical seventeenth century fly fisherman used a twisted horsehair line, tapered from seven hairs or more at the thickest part down to three hairs or less at the point. All lines were home-made, and although horsehair was the rule, pure silk, and silk/horsehair mixes were used on occasion. The line was usually fixed to the top of the rod, in which case the length was less than twice the length of the rod. Some anglers allowed the line run free through a loop at the tip of the rod, the free line being held in the angler's hand..” A Fly Fishing History by Dr. Andrew Herd

The availability of fly patterns, and differentiation by region significantly expanded during that period. Charles Cotton lists sixty five trout flies in his writings, covering every month of the year.

The following century brought about incremental innovations to different components. Untreated gut began to be used as a leader, running rings along the length of the rod became available, so that line could be fed, and rudimentary reels came into use.

The western fly fishing kit with which we are currently familiar did not come into full existence until the late 19th century. With improvements to line and rod resigns, false casting and the upstream casting of dry flies became possible. Reels finally began to resemble the ones we see today. The ability to cast the line over longer distance lead to shortening of the rod to lengths near ten feet and below. “The years 1851 to 1900 were a time of enormous change in the fly fishing world. In those fifty years, the conventions of centuries would be swept away. The false cast was discovered, the dry fly technique emerged, split cane rods were perfected, and reels that we would appreciate as "modern" appeared. In 1851, there were those who fished the fly and bait using the same rod. By 1900, specialised rods for dry fly fishing were on the market, and no-one would have dreamed of using a fly rod for anything other than its intended purpose…The wind of change began to blow in 1857, when Stewart, a young Scotsman, advocated upstream wet fly fishing with for 'a light stiff, single-handed rod, about ten feet long.' This, the discovery of the false-cast early in the decade, and the beginnings of dry fly fishing, began the trend towards shorter trout rods that led to the nine to ten foot split-cane rods of Halford's generation.” A Fly Fishing History by Dr. Andrew Herd

Tenkara Fly Fishing:

Tenkara is “a Japanese method of fly-fishing, which uses only a rod, line and fly”. TankaraUSA. The basic definition of tenkara fly fishing is easy to give, i.e. it is fly fishing without a reel, but a more detailed definition presents a lot of problems. The reason is that there is a lot of debate about exactly what the defining characteristics of tenkara actually are. When it comes to both equipment and technique consensus is hard to find on what is “true tenkara” and what is not. The question becomes even more problematic because what is considered tenkara in Japan is not always the same as what is considered tenkara in the US.

The first recorded mention of tenkara fly fishing comes from Sir Ernest Satow in 1878. In his diaries on July 24, 1878 he writes “Last night we had for dinner capital fish called iwana caught in the Kurobe-gawa, with a fly made of cock’s feathers, weighing ¾ lbs.” A Diplomat in Japan Part II: The Diaries of Ernest Satow, 1870-1883, 2009. Combined with the fact that Sir Satow spent much time traveling in high mountain areas, including the time when the above passage was written, it is generally accepted that this is the first written account of tenkara fly fishing.

Now, obviously tenkara fishing did not originate with Sir Satow. It is speculated that it dates back to the 7th century, or even further back, but as tenkara was a fishing method primarily used by villagers and small scale fishermen in the mountains of Japan, who were largely unable to write, no record has survived.

It is also important to note that while records of tenkara fly fishing are rare, there are well documented accounts of other forms of fly fishing or kebari turi in Japan. The most prominent method was ayu fly fishing, which was practiced in the lowlands, and was adopted by many of the samurai. Those forms of fly fishing involved the tying of intricate flies, which elevated the craft to an art form.

Even the term “tenkara” is an invention that originated in the 19th century. Clearly the form of fly fishing exited prior to that point, but the term can not be traced much further back, and was likely created to describe an existing for of fishing.

The equipment of the tenkara fisherman seems to have consisted of a long bamboo rod, of about fifteen to twenty feet in length. The line was made of braided horse hair.

It is difficult to speak of “true” tenkara because there probably wasn’t such a thing until very recently. Tenkara was a commercial form of fly fishing practiced in villages in high mountain areas of Japan. The defining characteristic of the fishing method during that whole period of its development was to simply catch fish. As a result, people did whatever produced the highest yield. There was little focus of the sporting aspect of the activity or any philosophy behind it. It is likely that after the 17th century, tenkara began adopting some elements from other forms of fly fishing such as ayu, which perhaps lead to some degree of stylization. Very likely however, tenkara did not emerge as a unified style of fly fishing until very recently when it could stop being a tool for commercial fishing, and could become a sport or leisure activity.

In an interview given by Yoshikazu Fujioka to Jason Klass on January 23, 2013, he states “Although this is my view, the history of fishing started in order to obtain food. Especially “kebari fishing” in the mountain village in Japan has been performed in order to obtain fish efficiently. (But I think “kabari fishing” that court nobles and a samurai performed at the Edo period had the element of game.)…There is the rule in fly fishing but there is not it in tenkara fishing. Young people are interested in flyfishing or lure fishing. I think that it is largely based on fashionability or the element of game. Those elements are not in tenkara fishing so much. I am thinking that in order for tenkara fishing to become popular, fashionability or the element of game become the key.”

The utilitarian nature of tenka fishing makes it difficult to speak of what it actually is without first turning it into a sport and adding stylized elements. That has been done to a large degree in the US, but from what I have seen, is not the case in Japan.

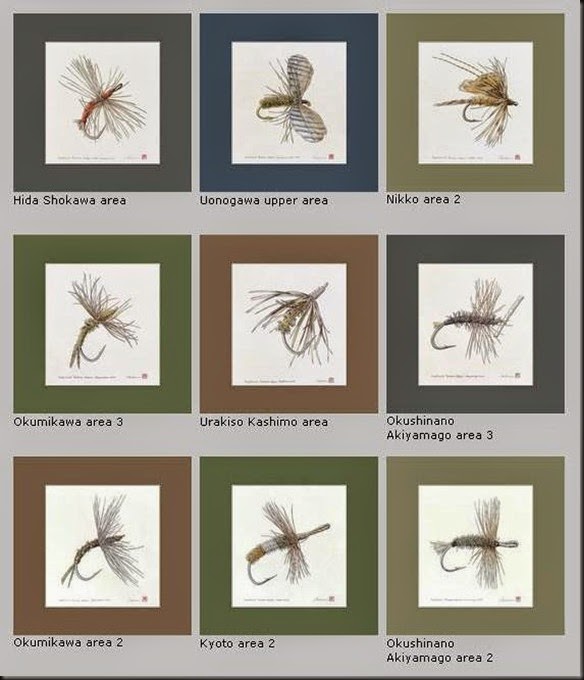

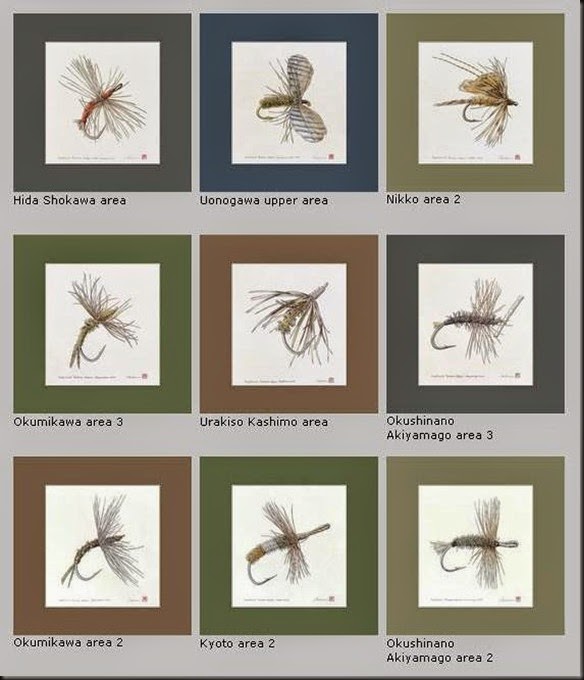

In our modern attempt to discover “true” tenkara fishing, we have distorted many elements of this very diverse form of fly fishing. For example, there has been quite a bit of talk about how tenkara fly fishing uses only a single fly, called the kebari. That notion is very far removed from the roots of tenkara. It is true that early accounts of tenkara fly fishing seem to imply that fisherman used a very limited assortment of flies, or even just one design. That however is not an element of tenkara, but simply a product of where the fishing was done. Most tenkara fishermen fished in the streams near their own village. As such, they knew what fly worked, and used it repeatedly. Additionally, as with all fly fishing, there is an understanding that if your presentation is poor, no fly design is going to help you. Again, that is not an element of tenkara, but rather is an element of all fly fishing. The reality is that there were and still are many different variations of flies used in tenkara fly fishing, and they varied from village to village and from stream to stream. Here are just a few examples provided by Yoshikazu Fujioka:

The notion that a tenkara angler would insist on using the same fly while fishing from the mountain streams of Japan to the waters of the Delaware River, despite of what the fish are actually biting on, is completely inconsistent with the origins of tenkara, i.e. commercial fishing, and is a modern element of sport that has been added in recent years. Conversely, the notion that a western fly fisherman continuously changes flies throughout the day is absurd. It is very common for a western fly fisherman to fish the whole day with a single fly for the same reasons why a tenkara fisherman may do so.

Just like with western fly fishing, recent technological development have also altered the fishing method. The introduction of carbon fiber rods and monofilament line, have made things like overhand casting fully possible with a tenkara set up, something which would have been challenging with a bamboo rod and braided horse hair line.

So, why did I write all of this? My goal was to try to get to the core of each form of fly fishing by examining (however briefly) its origins and evolution. By doing that, it becomes easier to see what each form of fishing is all about, what it’s practical aspects are, and consequently, which of the things you read about each form of fishing are just fluff and hype.

Keeping that in mind, I will go through some of the relevant points I have seen made numerous times regarding both forms of fly fishing, and I will give you my opinion on them:

- Western fly rods take a very long time to set up compared to tenkara

Not true. Even as a beginner, it takes me less than 2 minutes to take out and set up my western style fly fishing kit. If it is taking you much longer than that, you have problems much larger than your fly fishing kit. Putting the reel in place takes about 10 seconds, and threading the line takes another 20 seconds. Even at a super relaxed pace, you should be completely set up in a few minutes. I’m sure that with a tenkara kit you can shave off a few seconds, but that’s about it. TenkaraUSA has a slogan “Only a rod, line and fly.” I suppose Orvis could have one that goes “Only a rod, reel, line and fly”. You have to look very closely to tell the difference.

- Tenkara fishing (as a set up) is cheaper than western fly fishing

No it’s not. The way people who make this point justify their assertion is to take a cheap tenkara rod and compare it to a top end western fly rod. If we look at comparable set ups, the two cost about the same. For example, the Patagonia Simple Fly Fishing 10’6” tenkara kit costs $280. An Orvis Clearwater outfit, including a 9’ rod, reel, fly line, backing, and case, will cost you the exact same amount. The Orvis Encounter outfit will run you about $160 for the same set up. Sure, I can spend thousands of dollars on a western fly fishing kit, but I can do the same for a tenkara kit. Sure, a tenkara set up made in China costs $300; how much would it cost to have a custom rod made in Japan by a respected maker and delivered to the US?

- You can not cast a tenkara rod

Yes you can. You can cast a tenkara rod the same way you can cast a western fly rod. The main difference is that with a tenkara rod you can not extend the line during a cast (or at any other time for that matter). However, the same way you can cast a western fly rod with a fixed amount of line let out, so can you do it with a tenkara rod.

- The fixed line limits tenkara rods to small bodies of water

Not exactly. It is true that the line is limited, but with a long tenkara rod (think 13’6” and up) you can cast just about as far as you would want to. All things being equal however, and using rods of the same length, the tenkara set up is at a disadvantage when trying to cast longer distances. The limited casting distance is indeed an issue, and can not be ignored, although in most cases it’s significance overrated.

- Tenkara kit is simpler than a western fly fishing kit

No it’s not. Each kit can be as simple or as complicated as you want to make it. Sure, western fly fishermen carry tons of gear, but that is not because of the method, or the set up used, but rather because they are looking for what works the best at any particular moment. You can fish a single fly on a western fly rod for the rest of your life just like you can do it with a tenkara rod. Similarly, you can make the tenkara kit as complicated as you want. The only real savings in terms of complexity of gear is the reel. However that’s one of those infomercial moments. Putting a reel on your rod is something that takes the average person under a minute and shouldn’t offer any challenge.

Similarly, selecting the equipment is just as challenging with either set up. It may be intimidating to walk into a fly fishing shop and start trying to select the right rod for you, so the slogan of “Only rod, line and fly” may seem very appealing. If you look however, you will see that there are just as many, if not more variations in tenkara rods than there are in western fly rods. Trying to balance the length, stiffness, and action index of a tenkara rod for your purposes is no easier than selecting a western fly rod.

- Tenkara kit is lighter and easier to backpack with

Somewhat. Just like with anything else, you can make selections to lower the weight of your kit, but neither kit is necessarily lighter. My western fly rod weighs 2.5oz, my reel weighs 3.2oz, my fly box weighs 1.7oz, and my rod case weighs 1.8oz. Together with line and a roll of tippet, the whole kit is under 10oz for a 5wt 9ft set up. If I wanted to I could make the kit even lighter. Can you go lighter with a tenkara kit. Probably. Can you make a tenkara kit much heavier? Of course you can. The tenkara set up saves you the weight of the reel, so if you are just as careful in your selections, a tenkara kit should end up being a few ounces lighter.

- Tenkara replaces gear with skill, making you a better fisherman

No it doesn’t. This now enters the realm of spiritual mumbo jumbo. A tenkara set up leaves out only a single piece of gear, the reel. That’s it. Everything else has a one-to-one equivalent on each set up. To compensate for the lack of reel, tenkara rods are generally longer. Whether you are skilled has very little to do with the rod you are using.

- Tenkara allows for better control of the fly and for a better presentation

No it doesn’t. A particular person might be better with one set up rather than the other, but there is nothing inherent in the set up that makes control or presentation any better. Sure, if you are using a 13’6” tenkara rod, you will be able to more accurately place the fly at 15’ as compared to someone using a 8’6” western fly rod, but if we make things equal, and give the Tenkara fisherman a 8’6’ tenkara rod, the accuracy and presentation will be just about the same. Even with the different rod lengths, if we are talking about casting at 30’, the accuracy is about the same. On the other hand, I don’t see how it would be easier to position a fly five feet away from me with a 13’6” tenkara rod as opposed to a 8’6” western fly rod. If you have trouble placing a fly at a particular distance, then you can get a longer western fly rod just like you can a longer tenkara rod. Western style fly fishing variants like Czech nymphing are a perfect example where a longer western fly rod is used to present the fly using only the leader.

So, I’ve written all of the above to say the following: If your interest is catching fish, rather than participating in any sanctioned fishing related sport, then the differences between the two fly fishing methods start to become very vague. Each set up allows you to fish how you want to fish. If you like short rods, you can get a 8’6” tenkara rod as well as a western fly rod. If you like longer rods for better positioning your fly at longer distances, then you can get a 12” tenkara rod as well as a western fly rod. If you want to fish with a single fly for the rest of your life, you can do that with a tenkara set up as well as a western fly fishing set up. If you want to tie and use multiple flies, you can do it with either set up. By selecting the right gear, each set up can be specialized for fishing at close range in small bodies of water, or at long distance in large bodies of water. Each set up can be very expensive, or inexpensive (relatively speaking) depending on what quality you want. If you use the same techniques, each set up is just as easy or complex to use. Casting can be just as easy or just as complex with either set up depending on what you are trying to do.

The history of the two forms of fishing is very similar. A 18th century tenkara fly fishing set up is nearly identical to a 15th century western fly fishing set up. So, to claim that any particular characteristic is unique to tenkara fishing or western fly fishing is a stretch. In fact, in the late 19th and early 20th century, the same comparisons were being made by anglers. On one hand you had the older fly set ups (then western) of a long rod and line without a reel, and the more recently developed shorter rod and reel designs. The later won out for what I’m sure were complex reasons. Either method however can be used to give you the desired effect. How you fish and where you fish might guide you to one form or the other. If you fish at fixed distance, whether it be short or long distance, a tenkara rod will work just fine. If you want to make a lot of transitions between short and long distance then a western fly set up might be a better call. Everything else you can adjust and modify to suit your needs. The fish don’t know if your fishing style is “pure” and “true” or not.

That is not to say that there are no differences between the two methods, or that both would be equally suited to every person and every situation. My point is that the dramatic disntinctions that are made so often in justificaiton for one’s gear choice don’t always line up with the facts. I know what set up I would chose if I could only have one rod, and it wouldn’t be a tenkara set up. That being said, I’m sure I can be just as poor of a fisherman with a tenkara set up.

This of course is just a practical perspective on the subject from the view point of a beginner. How special you feel, or how meditative your state is when you use either method is a personal call.