Random thoughts on axes, knives, axe use, woodworking, bushcraft, wilderness survival, camping, hiking, and gear review.

Wednesday, December 30, 2015

How to Camp Out, by John M. Gould

Monday, March 3, 2014

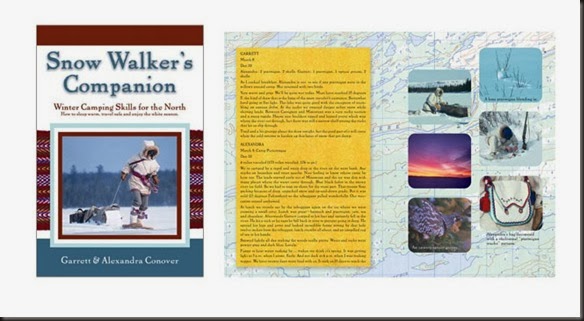

A Snow Walker's Companion: Winter Camping Skills for the North Review

As you guys have probably noticed, I try to do book reviews primarily for books that can be obtained for free online, so that you can easily get them. A Snow Walker's Companion: Winter Camping Skills for the North by Garrett Conover and Alexandra Conover Bennett is not in the public domain, and as such is not freely available. Even so, I thought it was worth a mention.

The book is currently in it’s third publication. It was originally released in 1995 with subsequent publication in 2001 and 2005. I have purchased two different publications of the book over the years, and have read it several times.

I first read the book years ago when I was developing an interest in more complex winter travel in the woods. Last year, I was again reminded of the book and re-read it. A Snow Walker's Companion has developed a cult following and is often sited as one of the best guides to winter travel. The book focuses on traditional methods for winter travel, which according to the authors are more efficient and reliable than modern methods that are overly focused on technology.

I must admit, I have refrained from writing anything about the book here because each time I read it, I was sure that I had missed or misunderstood something. The methods described seemed highly inefficient and unnecessarily burdensome for winter travel. Recently however, a fellow blogger provided a link to a video of a trip structured after the manner outlined in A Snow Walker's Companion, and even included Garrett Conover as one of the members. After watching the video with great interest, I felt secure enough that I had understood the book as it was intended and finally decided to write a review here.

As I mentioned above, A Snow Walker's Companion focuses on traditional methods for winter travel. According to the authors, those methods are the most reliable and efficient means for winter travel. As portrayed in the video, those methods culminate in a team of wool and canvas clad men, pulling heavily loaded toboggans containing large canvas tents with wood stoves, along frozen river beds and lakes.

Each time I read the book it struck me as rather condescending and dismissive of any other means of winter travel. Now, I am the last person to talk about being dismissive and condescending, so I will not begrudge the authors their attitude. However, it did strike me as strange that they would insist that this is the most efficient and reliable means of winter travel. I would certainly understand it if the authors simple like such traditional means of transportation during winter, or if they were doing it to recreate for educational purposes winter travel in the age of Shackelton and Nansen. I do find it perplexing however that they would insist that in light of all of the techniques and equipment we have developed over the last century, that this is still the best form of winter travel.

The most glaring reason why I found such an assertion to be a strange one is that the scope of travel afforded by the methods outlined in the book is so very limited. In effect, if you chose to travel in the manner outlined in A Snow Walker's Companion, you immediately restrict yourself to terrain that is limited to frozen river beds and lakes. Anything more than a ten degree incline, and travel is transformed into a heroic struggle, or outright impossible. That is not to mention travel up mountains, through densely forested areas, etc. It hardly seems like the “ultimate” travel method.

Leaving aside the absurdly limited terrain option left to us with this traditional form of winter travel, let’s look at the above video for more specific examples. I use the video because it was designed as an educational class developed based on the book, and had one of the authors as a member of the trip.

The video features a team traveling 62 miles (100 km) over a 10 day period. Each team member is pulling a sled loaded with an average of 150 lb (68 kg) of gear. Now, for any modern woodsman who is familiar with winter travel, those statistics will seem ridiculous. They will be even more shocking if one watches the video and sees the struggle endured by the team over these 62 miles. The short trip featured in the video is very similar in its factors to that completed by the authors of the book. They traveled 350 miles (563 km) across Labrador along frozen rivers in the manner outlined in the book. The trip took (if memory serves me right), about 60 days.

I say it would be shocking to a modern woodsman because for anyone familiar with modern techniques and equipment, traveling 62 miles over 10 days on level and clear terrain like that necessitated by the methods of travel outlined in A Snow Walker's Companion and seen in the video, would be considered a leisurely, relaxing trip. In fact, even at moderate pace, such trip can be completed without any effort in half the time. More so, a modern team can complete the same trip with a quarter of the gear. It would not cross the mind of any modern woodsman to go on a 10 day winter trip with 150 lb of gear. Counting food and water, a modern woodsman would have a pack at the beginning of the trip under the same conditions of no more than 40 lb (about 15 lb of gear, 20 lb of food at 2lb per day, and about 4 lb of water).

Now, let me make it very clear, when I say “a modern woodsman using modern techniques and gear” I do not mean any fancy electronics or motorized transportation. I mean a person on snowshoes with a tent a sleeping bag, a backpack, etc. Using modern techniques and equipment, a woodsman can take that 150 lb of weight that was used for a 10 day trip with the methods outlined in A Snow Walker's Companion, and can stretch them out for a 65 day trip. The difference is staggering.

Just for rough comparison purposes, Paolo Rabbia just completed a 435 mile (700 km) traverse across the Pyrenees, with an elevation gain of 10,499 ft (3200 m). He completed it in 29 days, carrying a 44 lb pack (20 kg). All of this was done on some of the toughest terrain imaginable. Now, I know Paolo Rabbia is not an average person, but an average person would have certainly been able to duplicate the results if traveling on frozen river beds and lakes.

I know some of you were not happy with the above comparison, so I figured I would toss in another one. Ray Zahab, Ryan Grant, Stefano Gregoretti and Ferg Hawke just completed a 100 km (62 mile) crossing of Baffin island. They did it in 48 hours, pulling 50lb sleds. The crossing was entirely unsupported. Again, an extreme example, but one showing what is possible using modern techniques.

Considering all of the above, I continue to find it strange that the authors of A Snow Walker's Companion insist that the form of winter travel they have outlined is somehow superior to other forms of winter travel.

Perhaps one could insist that the form of travel outlined in the book is more comfortable than modern forms of travel, with a nice large tent and a fired up stove. Sounds good in theory, but as the video shows, almost every day, from dusk till dawn, the team is struggling pulling heavy sleds, over lakes that can not support the weight, hacking paths through trees, etc. Hardly seems like a relaxing trip. A modern woodsman can complete each day’s travel in half the time, leaving plenty of time for a nice fire, a cooked meal, and relaxation.

And let’s not forget, the modern woodsman can go wherever he pleases. He is not locked to frozen rivers and lakes. If he so chooses, he can go over a mountain, through a valley, into a dense forest, etc.

Now, all that being said, A Snow Walker's Companion is a good book. If you are interested in traditional winter travel, or are a historical recreationist, the book is a wonderful resource, as long as you can ignore the perplexing assertions about how that form of travel is the best. The book does a good job describing the methods required for such traditional winter travel, and even provides resources where such traditional gear can be obtained. Within the scope of the type of winter travel it describes, it is an excellent guide. So, if you are interested in traditional forms of winter travel, this book is for you. If you are interested in historical recreation, then this book is for you. If you thought Shackelton was the man, and you want all of your winter trips to resemble his attempt at the South Pole, then this book is for you.

The downside of the book, of course is that it is so limited in scope. If you are interested in any other type of winter travel, which does not involve teams of men pulling heavy sleds along frozen rivers, then the book offers very little. Not only that, it is outright dismissive of any such forms of travel. So, if you don’t want to pull a 150 lb sled for a 10 day trip, this book is not for you. If you want to carry all of your gear in a backpack, this book is not for you. If you want to go anywhere where the terrain is not 100% level and clear of any vegetation, then this book is not for you. If you want to travel in an area where trees are not abundant, then this book is not for you. If you think that we might have learnt something about winter travel in the last century, and you want to take advantage of that knowledge, then this book is certainly not for you.

P.S. since my last purchase of the book, it seems like the publisher has run out of copies, and the price has skyrocketed. Hopefully this review would serve you as a decent guide as to whether you want to fork over the current $150 price.

Tuesday, August 6, 2013

Fire-Making Apparatus in the US National Museum, 1890

A few days ago a fellow blogger, Master Woodsman, posted a very interesting link to a document written by Walter Hough and published in 1890, cataloging and explaining in good detail different friction fire methods that were documented by the museum at that time.

This document is one of the best sources of information I have ever seen on historical use of friction fire making techniques and equipment. Not only does it provide illustrations of the tools used, it offers accounts of exactly how these tools were used and stored.

If you have any interest in friction fire making, this documents is a must read. It offers many nuances and details that have been largely forgotten over the years. You can read and download the document in different forms for free, here, or just view the PDF here (takes time to open).

Friday, June 15, 2012

An Eskimo Strike-a-Light

A few day ago, Woodsrunner posted a link to a great piece of writing, detailing a fire lighting technique used by certain Eskimo groups. The technique closely resembles the flint and steel method, but predates the use of steel/iron strikers. It is also interesting to note their tinder selection, and some areas where technology has effected the technique.

In the interest of not loosing track of this document, I have uploaded it myself. You can download it here.

Wednesday, April 25, 2012

Tool and Symbol: The Success of the Double-Bitted Axe in North America, by Ronald Jager

This is an article published in 1999 in Technology and Culture. In the article Jager discusses the ascent of the double bit axe in America and some potential reasons for its popularity. He makes a few brief guesses as to potential practical advantages, and while he makes a technically correct point about the aerodynamics of a double bit axe as compared to a balanced single bit axe, I am not sure it translates to any practical and therefore competitive advantage. I found his discussion of the social forces behind the transition however very interesting. I think he makes a good point that the choice of even something as practical as a tool can have nothing to do with practicality. I think we see that a lot today in our own outdoor community.

The article is available on JSTOR if you have an account, or you can get a copy here. I want to thank Joe from Woods Monkey for providing it to me.

Wednesday, April 4, 2012

Scrambles Amongst the Alps, by Edward Whymper

On July 14, 1865 Edward Whymper and his party made the first successful climb of the Matterhorn, the highest peak in the Alps. His book, written in 1871 documents the climb and the unfortunate descent that lead to the death of several members of the party.

While the book can be too technical at times for people who are not climbers, it gives us a good amount of information about the gear, clothing, and techniques used in the early days of mountain climbing.

To my knowledge the book is in the public domain, and a free copy can be obtained here, here, and several other places online.

Monday, March 19, 2012

Axe Books and Books About Axes

Recently I had a comment on a thread asking for some older books dealing with the subject of axes. I decided to put together a short post on the subject instead of trying to cram it into a comment response.

Civil War camp of the 6th N.Y. Artillery at Brandy Station, Virginia, 1864

To begin with, as I have mentioned before, my blog and what I do and write about here is simply a hobby. I am not a historian, nor do I work in a lumber yard. Everything that I write about is based on information I have been able to find from people, books, and a lot of experimentation.

There are a few books that I have come across on the subject of axes that I have found useful, so I’ll share them with you here.

First however, remember that if you are looking for historical data about axes, your primary sources will not be books. I have not been able to find anything on the subject prior to the early 1900s. My sources of information for that earlier period have been photographs, in particular Civil War photographs, and images of old advertisements. You also often have to read between the lines of books unrelated to the topic, to pick up some information about the tools that the author mentioned unknowingly.

In the early 1900s we start to get some literature on the subject of axes. I find that a lot of the literature that follows largely just repeats the information published during that period.

ANCIENT CARPENTERS’ TOOLS, Together With Lumbermen’s, Joiners’, and Cabinet Makers’ Tools in Use in the Eighteenth Century, by Henry C. Mercer – This book was first published in 1929, and to date remains one of the most influential works on the subject. Clearly the book covers a much wider range of tools than axes, but it has some excellent section on the subject, along with some good photography of the tools. Most subsequent books tend to repeat the information provided by Mercer here. Unfortunately I find that further research, with few exceptions tend to be lacking.

THE AXE MANUAL OF PETER McLAREN America’s Champion Chopper, by Peter McLaren – This book was first published in 1929. Almost certainly the book wasn’t actually written by McLaren himself, but it was published by Plumb when McLaren became a champion using their axes. The book does not discus any history, but instead focuses on technique, use and maintenance. It is an excellent source of information, and you can get it for free here.

WOODSMANSHIP, by Bernard S. Mason – The book was first published in 1945. It also focuses on axe use and maintenance among some other tools. It is a great source of information and can be obtained for free here.

THE HISTORY OF WOODWORKING TOOLS, by William L. Goodman – This is a book that was published in 1964 and contains quite a bit of independent research, providing very useful information on the early stages of axe development. Goodman also has a series of excellent articles in the Journal of The Institute of Handicraft Teachers.

AMERICAN AXES, A Survey of Their Development and Their Makers – The book was first published in 1972. It covers some history about axe development, and also has some information on specific, historically significant, manufacturers. I find the information to be good, although I wish there was more debt to it. I would have loved for this book to have been twice the size it is.

THE AXE BOOK, The Lore and Science of the Woodcutter (Formerly published as Keeping Warm With an Axe), by Dudley Cook – This book was published in 1981, and covers topics of axe maintenance and in particular axe use. When it comes to axe use, it covers the topic with more debt than most other books, and in that respect is quite good. There are some aspect of the book with which I outright disagree, specifically his discussion of handles, but that should not detract from the other excellent parts of this book.

AXE MAKERS OF NORTH AMERICA, A Collection of Axe History and Manufacturers, by Allan Klenman – This book was published in 1990. Its main focus is an encyclopedic description of American axe manufacturers, with a few pages dedicated to some foreign companies. It is not a complete listing, but is an excellent resource.

AN AX TO GRIND, A Practical Ax Manual, by Bernie Weisgerber – This book was published in 1999 by the US Department of Agriculture. It covers a bit of everything, from history to axe use. It is a companion edition to a set of videos with the same name. You can see the videos here, and the book itself here.

YESTERYEARS TOOLS – This is actually a website. I ordinarily wouldn’t include a website in this list, but it is simply an excellent source of information. In a similar fashion to Axe Makers of North America, the website provides information on different axe manufacturers and more importantly, graphics of many of the logos used for their brands. You can see the website here.

Aside from the above books which are at least in part focused on axes, there are many other books where a simple mention of an axe can give us a glimpse into a history that has been lost. Some of my favorite books, which are not on the subject of axes, but can provide some contextual information are:

WOODCRAFT, by Elmer H. Kreps – The book was first published in 1916 and along with being one of my favorite books on the subject of bushcraft, contains some excellent bits of information about axe use and maintenance. It can be obtained for free here.

THE BOOK OF CAMPING AND WOODCRAFT, by Horace Kephart – The first edition of the book was published in 1906 and the second, more extensive edition in 1916. The book is very long and has a short section on axes, but the most useful bits of information about axes can be found scattered throughout the rest of the book. A free copy can be obtained here.

As I mentioned above, some of the best information you will find on the subject is through independent research. Unfortunately too much information just gets repeated without too much thought or support. Don’t take what you read in any book as the final word on the subject. If something doesn't make sense, question it, no matter who wrote it.

Monday, September 12, 2011

Through Siberia, The Land of the Future, by Fridtjof Nansen

This is a book documenting the journey of the Norwegian explorer through Siberia. The book is not a bushcraft tutorial, but much can be learned from its pages and a good number of photographs of the indigenous people. The book was published in 1914.

To the best of my knowledge, the book is in the public domain, and a copy can be obtained here, here, and a number of other places online.

Friday, May 13, 2011

Woodcraft by E.H. Kreps

To the best of my knowledge this book is in the public domain and a copy can be downloaded here, here, and a number of other places online.

Tuesday, April 26, 2011

The Axe Manual of Peter McLaren

The manual is a short booklet on axe care and use. It is very well illustrated and provides great information in a very compact and direct way. As far as I know the book is in the public domain, and a copy can be found here (PDF), here and a number of other places online.

Wednesday, March 9, 2011

Handtools for Trail Work

To the best of my knowledge, this book is in the public domain, and a copy can be downloaded here (PDF), here, and a number of other places online.

Monday, February 21, 2011

Camping and Woodcraft Gear from the Past

Specifically, note page 58, where Kephart’s kit is featured. In my original post I had indicated that the kit was made out of tin, as per the description in the museum, but the catalog specifies that most of the parts were made out of aluminum, and the cup and utensils made out of steel. It is interesting to note that Kephart had replaced the steel utensils that came with the kit with wooden ones.

We have to remember that while we read of the adventures of people like Sears and Kephart, these are people who were doing exactly what many of us do these days. They were recreational outdoorsmen, who spend as much time thinking about their gear, and clearly wasting as much money on it as we do.

Monday, February 7, 2011

Complete Guide to Home Canning

To the best of my knowledge this book is in the public domain, and a copy can be obtained here, here, and a number of other places online. The book has several chapters, which can be downloaded as PDF files individually.

Thursday, January 27, 2011

Woodsmanship, by Bernard S. Mason

To the best of my knowledge, this book is in the public domain, and a copy can be obtained here (PDF), here, and several other places online.

Wednesday, January 5, 2011

Crosscut Saw Manual, by Warren Miller

To the best of my knowledge, this book is in the public domain, and a copy can be obtained here (PDF), here, and several other places online.

Tuesday, November 23, 2010

Camping and Woodcraft by Horace Kephart

The book is very comprehensive, and as a result, large sections have become largely irrelevant. For example, he goes into great detail about tents and sleeping bags, technology which has been outdated by about 100 years. There is however a lot of very good and relevant information on the subjects of woodsmanship.

As far as I am aware, the publication is in the public domain. A copy of The Book of Camping and Woodcraft can be obtained here, and a copy of Camping and Woodcraft; a Handbook for Vacation Campers and for Travelers in the Wilderness can be obtained here, and a number of other places online.

Tuesday, November 16, 2010

An Ax to Grind: A Practical Ax Manual, by Bernie Weisgerber

To the best of my knowledge, this book is in the public domain, and a copy can be obtained here (large PDF), here, and several other places online.

Monday, October 25, 2010

Flint Knapping: Articles, Tips, and Tutorials from the Internet

As far as I am aware, this information has been released into the public domain, and a copy can be obtained here and here.

Thursday, September 16, 2010

The Ten Bushcraft Books by Robert Graves

It is on point and sufficiently illustrated. The publication manages to pack a large amount of information in an easy to read form. It is well worth a look.

As far as I am aware, the publication is in the public domain, and a copy can be obtained here, here, and a number of other places online.

Thursday, August 12, 2010

Shelters, Shacks, and Shanties by Daniel C. Beard

The instructions are not detailed, and same of the shelters pictured would be very difficult for the average woodsman to construct in a short period of time, following just the instruction in the book. With time and practice however, the ideas that can be obtained from this book, can significantly improve your improvised shelters.

As far as I know, this manual is in the public domain. A copy can be obtained here, here, and many other places online.