Okay, so the title is a bit misleading. I don’t mean to discuss the cost of gear, or even the environmental impact that may be caused by certain practices. What I want to discuss here is the limitations that bushcraft puts on us when out in the woods.

Recently I posted about how many people, including me, tend to do “bushcraft” in very inactive ways. We practice skills that never translate into use under actual fiend conditions. We can build natural shelters, start friction fires, carve anything that comes to mind, but we never leave the security of a camp site conveniently located next to the car. When we do actually go into the woods, we stop calling it a bushcraft trip, and then bring all of our tents, stoves, etc. Why isn’t bushcraft something that we use for all of our needs in the woods? After all, there are many within the bushcraft community who have mastered those skill, and even more who talk about how they have, even with a degree of disingenuous modesty. It is true that some areas have regulations that limit many practices, but there are many places where the full range of bushcraft skills can be practiced.

I was thinking about why that is the case, assuming of course, that it is in fact the case. The most immediate answer that hit me was “time”.

No matter how good we are, accomplishing tasks through the use of bushcraft requires time. Sit, and honestly think about how long it takes you to complete any particular task. How long does it take you to start a fire using a bow drill? I don’t mean just the spinning part; I mean, going into the woods with just your knife, finding suitable wood, carving out a set, collecting plant material, making cordage to use, collecting tinder, and then starting the fire.

What about making natural shelter? If you are planning on it being waterproof, and you want to make it so only using an axe, how many hours will it take to make one of those lean-to shelters we see in books. How long does it take you to gather enough material to build a two foot thick bow bed that will provide sufficient insulation from the ground?

How long does it take you to purify water using only your pot? Again, I don’t just mean the time it takes water to boil, but rather imagine that you are walking through the forest, and notice that your canteen is getting low. You decide to fill up. You stop by a creek. Now you have to strain it, build a fire, boil the water, and preferably let it cool down before drinking. Even assuming you had prepared your fire spindle and bow earlier, this will still be a significant stop. Now imagine doing it several times a day.

Now, if on top of that we add something like foraging for food, our time allocation just falls apart.

So, imagine the following bushcraft trip:

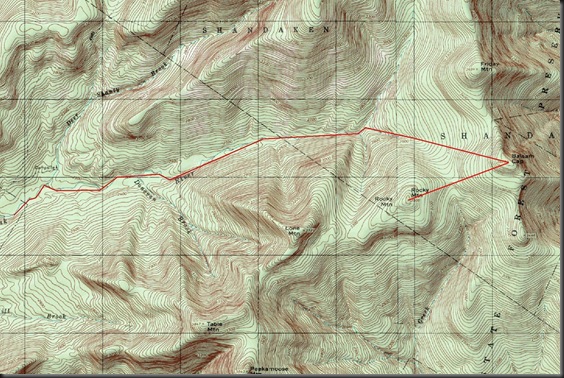

You set out into the forest, with a nice canvas backpack. Inside you have a metal billy can, a wool blanket, an axe and a knife, a canteen, some tea, sugar and rice. Nature will provide for everything else. You will thrive with the use of bushcraft. You will quickly make some cordage from nettles or other locally available plants; you will carve out your fire set; you will purify water along the way by boiling it, and at the end of each day, you will build a shelter from natural materials. Along the whole way, you will forage for food to supplement your small supply of rice. Now imagine you are doing this for a week, traveling each day.

The time required to complete each of those tasks will simply bring the trip to a holt. While each of those tasks is very doable, and most of us have performed them at one time or another, when combined in a realistic setting, they start to take their toll. Doing a trip like the one outlined here will require most of us to start working on setting up camp shortly after lunch. If our goal was to travel to any point, things would be very slow going.

That can’t possibly be right; you say! There must be some trick to it that additional knowledge will reveal. After all, how did people do it in the good ol’ days?

Well, they probably really didn’t. We have come to expect a level of comfort in the woods given to us by modern technology, that we now try to recreate through the use of bushcraft and natural materials. From what I have read, this was not the reality in the past. Building a lean-to shelter like the nice ones we see on TV was not the common practice. Reading the journals of trappers and explorers, when caught away from camp, it was a lot more common to see them huddled together under a buffalo hide, with the dogs sleeping on top of them for warmth; or sitting by the fire, using just their coat as protection from the rain. Water was virtually never purified, let alone making one of those nice “filters” from a birch bark tube filled with sand and charcoal. Fire starting materials were prepared and carried the whole duration of the trip, and meticulously guarded. Similarly, food was carried and even experienced trappers considered it a problem if their supplies ran out, not to mention running out of ammunition. As much as it is fashionable to say that “if you are roughing it, you are doing it wrong”, those were rough men, and they had rough lives.

Looking at more recent sources, Nessmuk, when on his 10 day trip through the woods, he didn’t build any of the shelters he had described earlier in the book. At the end of the trip he concluded that since he didn’t bring a tarp, he would have been in trouble had the weather turned. Certainly there were instances where shelters were built, and more elaborate projects undertaken, but usually not in the context of a lone traveler through the forest. The reason usually wasn’t lack of skill, but rather shortage of time.

So, in order to still be able to continue doing these outdoor pursuits and tasks within the necessary time limitations, most of us take one of thee approaches:

The first one is to start gradually replacing or adding items. The bow drill is already pre-made and carried, and if time is short, replaced with matches or a ferro rod; the natural shelter becomes a tarp; the three wool blankets become a sleeping bag, the bow bed becomes a sleeping pad, or hammock, etc. Use of natural resources decreases, but in exchange, we can set up camp quickly, which in turn allows us to go deep into the woods. At some point, we just start to call it backpacking.

The second approach is the one that has come to be defined as “bushcraft”, which is to allow for those activities by removing the mobility aspect from the hobby. It is not much of an issue that making camp will take most of the day, because none of the day will be spent traveling through the woods, neither on the first day of the trip, nor on any consecutive day. The craft then transitions from one that is used in practical settings, to one that is done for its own sake at a fixed location. After the bow drill fire is mastered, then comes the hand drill, then doing it with a really, really tiny bow drill, then making a fire while standing on your head, etc. The fire making process (as an example) loses it’s practical motivation, and becomes more of a sport.

The third approach, of course, is to start telling everyone that the reason we are not doing it is just because we are too busy. Being too busy to do something seems a lot more prevalent in our community than in other outdoor pursuits.

I, amongst many others have gone through periods where I have felt bad about this irreconcilable divergence in our options. The more “bushcraft” we do, the more natural materials we use, the more our trips start to look like backyard campouts. On the other hand, the more travel we do, the deeper we go into the woods, the more adventure we have, the less “bushcraft” we use. I am yet to find any meaningful way to reconcile the two approaches. My current method has been to use bushcraft to supplement my trips into the woods, rather than forego the trips in the pursuit of “bushcraft”. We’ll see how it works out for me in the long run.

Anyway, this is just my theory…Don’t take it too seriously. Keep doing whatever does it for you.